When you work at the National Air and Space Museum, you can’t help but keep a special eye out for aviation and space topics or references in popular media like tv shows, movies, or music.

So imagine my surprise and delight when I tuned into the third season of the television series Bridgerton and discovered that the third episode had an entire ballooning subplot! The scenes featuring the balloon became a topic of much discussion here at Air and Space, just as they did on social media – but perhaps for slightly different reasons.

Now, like any good National Air and Space Museum employee, I watched the episode with a healthy dose of skepticism, wondering how accurate the depiction of lighter-than-air flight in the 1800s was. So I reached out to the Museum’s resident ballooning expert, curator Tom Paone, to get some answers.

Balloonamania

Balloons are incorporated into the episode as the “event of the week” to bring the characters together. Members of the Ton (high society of regency England, derived from the French expression le bon ton) all head to the park to gather, gossip, and see and be seen under the guise of viewing the spectacle of a balloon.

One thing Bridgerton certainly got right was the interest in ballooning that began to sweep across Europe, especially France and England, in the late 18th century. The first balloon was launched in June 1783 by the Montgolfier brothers, and other important launches followed in quick succession, including the first launch of a balloon carrying living creatures (a sheep, a duck, and a rooster) that September, and the first human beings to make a free flight in a balloon that November. When two aeronauts (that’s what you call a person who travels by balloon or airship) piloted the first free flight aboard a hydrogen balloon in Paris on December 1, 1783, an estimated 400,000 people – about half the population of Paris – gathered to watch history be made.

File URL

“Expérience fait à Versailles le 19 Sept 1783,” c. Print, Engraving on Paper, Colored

Now referred to as “Balloonamania,” this intense public interest in balloons manifested as huge crowds, new fashion trends, and balloon-inspired products.

“The large spectacle nature of the gathering, as well as the excitement of the crowd, is certainly accurate to descriptions of balloon launches of the era,” said Paone. “They were an amazing sight for many, and a well-advertised balloon launch event would often draw thousands of people, especially in big cities.”

One potentially missed opportunity for the show to demonstrate the way Balloonamania swept across Europe is the incorporation of balloon-themed products like jewelry, snuffboxes, fans, hats, and more. “The fascination with ballooning permeated almost all facets of life, especially in France, and was heavily commercialized into almost any product one could imagine,” Paone noted.

Given the excess frequently demonstrated by the characters in the Ton, I would have loved to see more ballooning fashion in the episode.

Timing

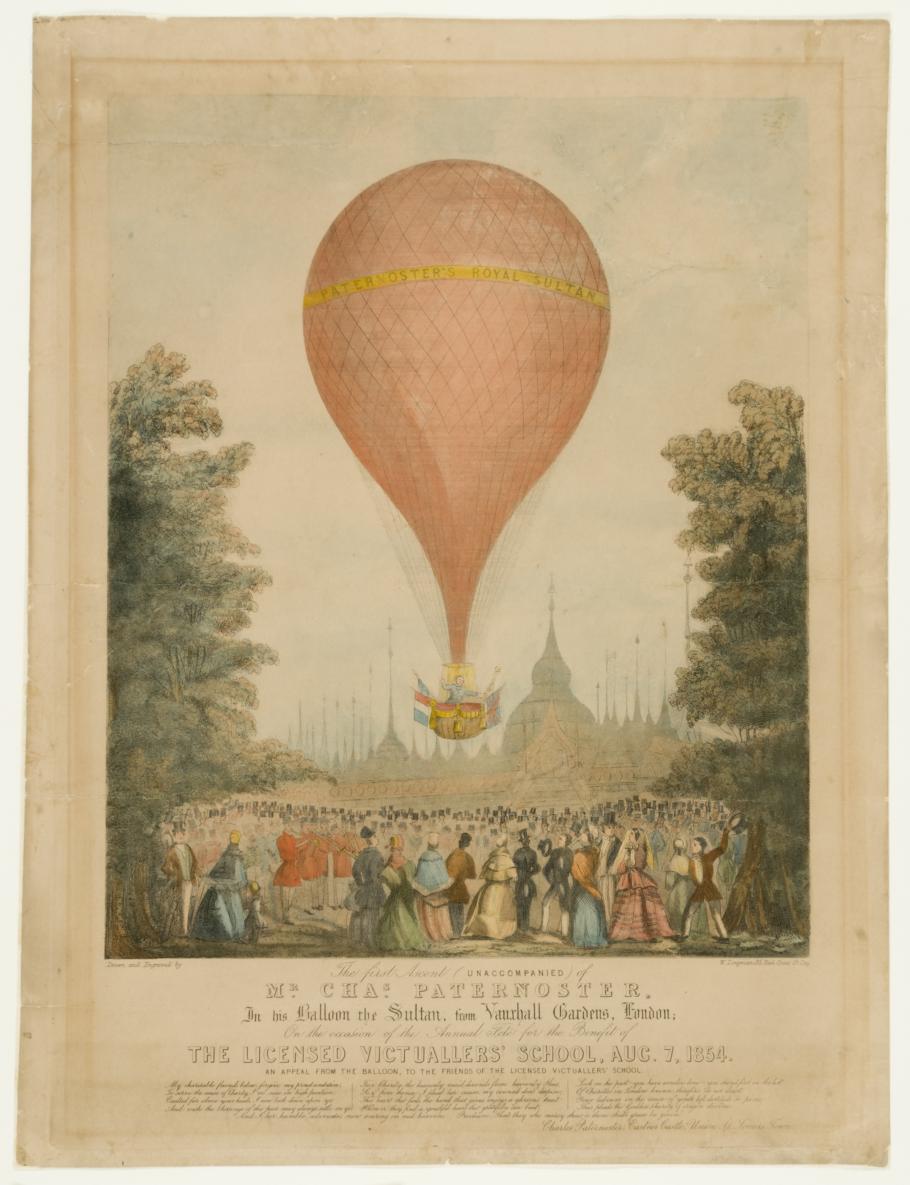

Knowing that the first flights of balloons started in 1783, I wondered whether the show, which takes place in the 1810s, was a bit behind the ballooning times. But Paone confirmed that the public spectacle of balloon launches continued well into the mid-1800s. One such flight, taking place in London in 1854, is depicted in a print in the National Air and Space Museum collection.

The crowd cheers the London ascent of the balloon Royal Sultan, flown by Mr. Charles Paternoster, August 7, 1854.

The Bridgerton Balloon

OK, so the crowd that gathered to view the spectacle of ballooning was accurate, as is the timing of when Bridgerton takes place. But how realistic is the actual balloon?

“I was impressed with the accuracy of the balloon itself to the period,” Paone said. For starters, “the balloon is decorated with bright colors and designs, which was very common at this time. The balloon also looks similar to illustrations of the ascension of the Montgolfier balloon of November 21, 1783.” Paone did note, however, that the basket seemed a little more fanciful than what you often read in descriptions from the time.

Oil painting on hard board. Ascension of the Montgolfier Balloon by Ethel Rich and Hugh Barclay Rich.

We also received a question from a social media user about why they couldn’t seem to see a burner on the balloon.

Paone had an answer to that: “When we think of balloons today, like those at the International Balloon Fiesta in Albuquerque, New Mexico, we often think of the large burners that are used to heat the air inside the balloons. Those burners, however, are a modern invention.”

Some early examples of balloons inflated by holding the envelope (the part of the balloon that is filled with hot air or gas) over a large fire and letting the rising hot air fill the envelope and provide lift. This severely limited the amount of flight time, because as the air cooled, the lift would dissipate. As a result, other balloons of the period depended on hydrogen gas to provide lift.

“The lack of a large fire in the scene implies that this is most likely a hydrogen gas balloon,” Paone said. “The long “tail” that hangs down near the basket would have been tied off to hold the gas once the balloon was filled. The balloon would have been held to the basket via the load ring, also shown in the scene, to help hold the balloon envelope in place.”

The hydrogen balloon from the third season of Bridgerton.

Reactions to Ballooning

Also included in the episode is a scene where various characters and members of the Ton talk with the aeronaut about the balloon, expressing some skepticism about the practicality of ballooning as transportation. I asked Paone whether this outlook would have been common at the time.

“Balloons were certainly a spectacle when they first launched in the 1780s and did spark much debate,” Paone shared. “People had numerous reactions to the balloons, from awe and amazement to distrust and distaste.”

Attack of the Balloon Basket

And that brings us to the big moment of the scene: the near disaster where the wind picks up and the tethered balloon begins to sway and move, careening toward our protagonist, who could be in danger.

But how real was that danger?

According to Paone, wind was certainly a serious problem for balloonists, though not necessarily in the way it was portrayed on the show: “Several balloons were ruined when they were blown into trees while inflated and tethered to the ground, causing them to rip,” Paone shared. He also noted that it would take quite a few crew members to hold down an inflated balloon that was no longer tethered, likely more people than was pictured in the show, given the size of the balloon. Turns out Colin Bridgerton alone would not have been able to control a balloon that was out of control.

But what about injury from an out-of-control balloon? “Balloons would be more potentially dangerous to those that piloted them than those watching on the ground,” Paone reflected, “especially since generally the balloon would be rising as well as moving with the wind, but I suppose it is possible.”

Paone also noted that many baskets were made of light materials, especially into the 1800s, making the risk of serious injury from balloon basket collision less likely. Which might explain why set designs went with the more fanciful (and sturdy) basket – to increase the risk level.

Bonus – King George III and Queen Charlotte’s History with Balloons

Colored etching of Professor Argand launching a hydrogen in the presence of King George III, Queen Charlotte, and the Royal Family in Windsor Park. On this occasion the King made a royal speech, short, true, and to the point. He said, “See, it goes.”

Queen Charlotte – the wife of real-life King George III — is a prominent character in Bridgerton (though the King is unwell in the series and is largely absent). That had me wondering whether King George III and Queen Charlotte had any history with balloons in real life. Paone confirmed that they did.

“We do know that George III was interested in financing balloon experiments in England at the time that France was making advancements in the field,” Paone said. “In November 1783, Swiss scientist Ami Argand demonstrated a small balloon to George III and family in Windsor. The king was incredibly interested in the demonstration.”

The Museum has an illustrated print in our collection showing that event.