The spectacle is human.

After nine episodes spent weaving a captivating web of political intrigue, history, and heartbreak powered by delicate character work, FX’s Shōgun takes its final bow with a conclusion as confident and seasoned as the rest of the series. Episode 10, “A Dream of a Dream,” untangles knotted threads in an extended denouement proving that this is the kind of television where the rewards don’t lie in visual spectacle. Shōgun‘s richest scenes are people talking. Such moments became event television of the classic watercooler variety, an accomplishment even more impressive since Shōgun, while tied to existing IP, is new territory for many. True to form, Episode 10 is daring in its refusal to take the path expected by a historical epic. There isn’t a traditional battle. The war portended by so many ends before it begins.

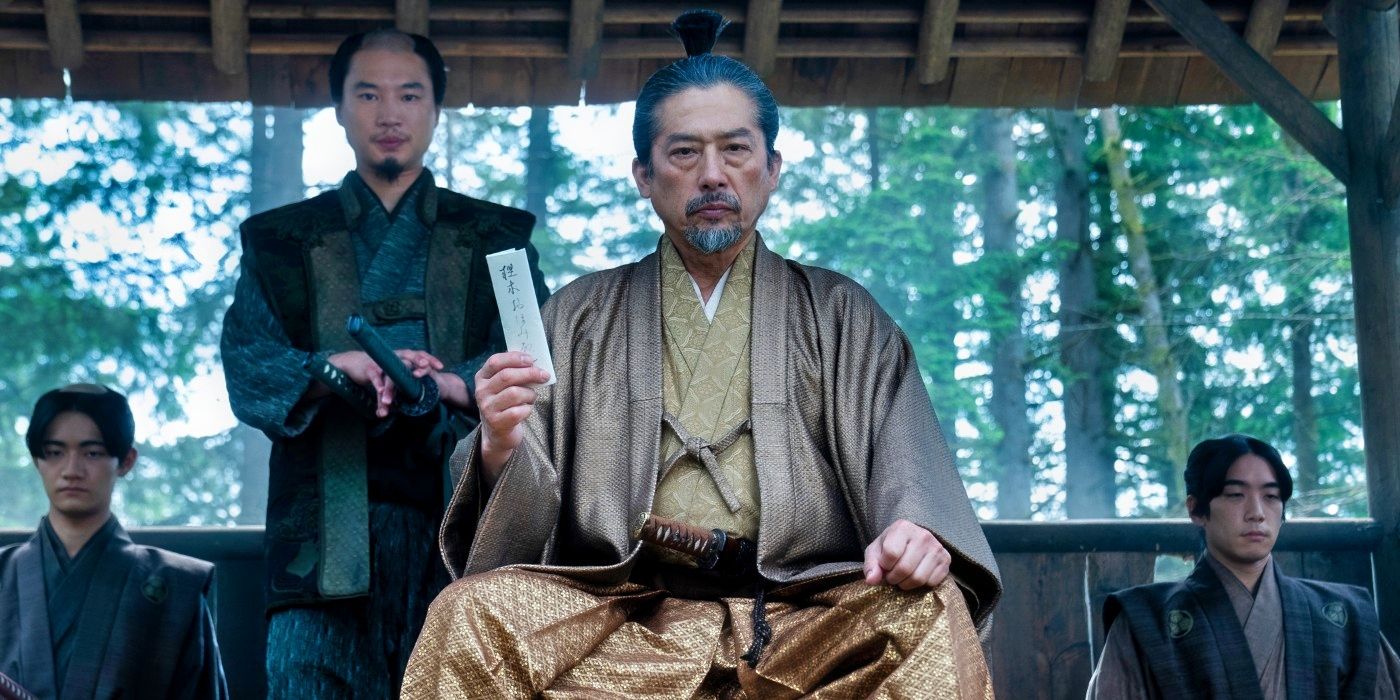

Just like watching the dissonant pieces of Lord Yoshii Toranaga’s (Hiroyuki Sanada) plan fuse into a clear picture, Shōgun‘s finale reveals it was never building toward a physical clash. The combat is emotional, and the spectacle is the story’s command over character. The clues about this clarity of vision were there all along. Overseen by co-creators Justin Marks and Rachel Kondo, Shōgun has always been about the people trapped inside a period of societal destabilization, how they respond to it, and the brutal human cost of re-establishing equilibrium. Episode 10, penned by co-writers Emily Yoshida and Maegan Houang, fulfills the requirements of a historical epic without the casual bloodshed. In fact, Shōgun goes out of its way to prevent unnecessary death. Crimson Sky is done. What’s left is the impeccable grace note that is “A Dream of a Dream,” a symmetrical and psychological finale where every resolution recalls its beginning and creates an undisturbed garden, instead of one proliferated by bodies decimated by cannon chain shots and samurai blades.

‘Shōgun’ Cares About the People, Not the War

Shōgun opens with one man’s dream, of sorts. Lost at sea and starving to death, John Blackthorne’s (Cosmo Jarvis) hubris convinces him that he can locate Japan (a feat unprecedented for England), destroy his Catholic enemies, and reap the rewards of Queen Elizabeth I’s gratitude. Shōgun ends with Lord Toranaga achieving his equally ambitious dream: a peaceful Japan that’s able to prosper after the tumultuous warring states period. Episode 10 counts the costs of realizing that dream, chief among them being Lady Toda Mariko’s (Anna Sawai) sacrificial death in Episode 9.

Pensively reflecting on how all parties react to Mariko’s absence reinforces Shōgun‘s dramatic purpose: examining that ageless, endless push-pull between fate and choice, sacrifice and greed, loss and gain, life and death. What creates a civil war? In Shōgun‘s case, it’s those who hoard power craving more. Whether it’s the gall of foreign nations trying to colonize Japan for its resources or Lord Ishido (Takehiro Hira), a man born into the peasant caste who’s willing to tear his nation apart if it elevates him, this is a confluence of the selfish.

With that in mind, how do individuals react to another impending conflict? Ishido might claim that the Council of Regents protects the realm, but Toranaga and his vassals are the only ones who perform that sacred duty. Toranaga rejects war. Japan itself does via the earthquake that follows Ishido proclaiming “war is inevitable.” Toranaga is as human and therefore as flawed as everyone else, but for him, power is a means to an end. His choices are predicated on his love for his country and his people. The goal is to minimize collateral damage instead of treating the overlooked and exploited as expendable. Conflict never dies: “Unless I win,” Toranaga says, deliberately echoing Blackthorne’s declaration from earlier in the season. “If you win,” Toranaga continues, “anything is possible.” That includes peace.

‘Shōgun’ Has Always Been a Character Study

Achieving peace demands sacrifice. Mariko’s death wins the war by preventing the war. In so doing, she turns Lady Ochiba no Kata (Fumi Nikaido), her childhood friend, to Toranga’s side. You see, Mariko also had a dream. Everyone in Shōgun tries to bend fate to their will. Ochiba vies for revenge and her son’s safety, which guarantees her own as his mother. Mariko fights to restore her family’s tarnished name. Usami Fuji (Moeka Hoshi) serves her liege lord as a stepping stone to freedom. In moral antithesis, there’s Blackthorne, Lord Kashigi Yabushige (Tadanobu Asano), and Ishido, who clamor for personal glory. Few are pure villains here except perhaps Ishido, and another series could depict him as a morally ambiguous antihero.

Still, he isn’t Toranaga the pacifist dreamer, who schemes for Japan’s sustained betterment. Toranaga’s allies agree, propelled into selfless and self-sacrificial action. How else could Shōgun conclude the battle for Japan’s future than with the emotional aftermath of a woman managing what an army couldn’t? Another battlefield clash damages the soul of a war-torn nation and distracts from the characters’ satisfying evolutions. If the winds of fate say war is inevitable, then Toranaga, ever the tactician, reads the winds and turns the tide accordingly. How fitting, then, that Ochiba concludes Mariko’s poem with “thankfully, the wind” — flowers might fall, but the wind carries them upright again. Equally fitting is how deeply Toranaga grieves Mariko. In the past, his opaqueness cast him in a ruthless light. With the chips fallen and the deed complete, the cracks show. He mourns the triumphant falcon he loves like a daughter, a woman who’s both his best weapon and his greatest loss.

Toranaga’s historical equivalent, Tokugawa Ieyasu, secured a long-lasting peace. Shōgun‘s ultimate question isn’t whether the cost is worth it, or who will assume the shōgun title. It dusts the psychological cobwebs off everyone who contributes to the outcome. It’s a character study by way of fictionalized history. These people have good reasons for their choices, if we use “good” in the framework of what creates a compelling drama.

Characters Find New Purpose in ‘Shōgun’s Finale

Ultimately, everyone in Shōgun is broken by something. How they re-emerge depends on them. For all that Yabushige and Blackthorne mirror, their paths diverge in the finale. The fact that Yabushige opening the door for the shinobi in Episode 9 had fatal consequences for Mariko shatters the world’s most slippery man into hallucinations and surprising honesty. Like Yabushige, Blackthorne admits his duplicity, but he learns and applies the lesson Yabushige can’t. Even though Blackthorne’s attempt at seppuku is a Western take on the ritual, it’s transformative. Defending innocent lives through protest is his first active choice in the entire series, and it means the hopeless and tetherless John Blackthorne is reborn. He evolves from fighting for his life to bitterly accepting his inevitable murder, then empathetically adopts Mariko’s words — “we live, and we die” — as the cornerstone for what he thinks is his last stand.

Blackthorne can’t fully integrate into Japanese culture, and he shouldn’t. What he can do is de-centralize himself from this narrative. He dedicates himself to a purpose larger than his own life, even rejecting an alternate reality where he returns to England and clings to Mariko’s memory on his deathbed. He surrenders her cross to the ocean and helps Fuji do the same with the ashes of her husband and son. Fuji, the picture of healing endurance, finds solace in Blackthorne’s idea that the ocean keeps our lost loved ones close.

Indeed, Mariko’s loss oscillates through the ocean waters, the water of Japan’s fate, and the episode. Her death poem, and her life, make one hell of a bonfire. It’s subjective whether the ashes of that fire guarantee everyone a happy ending. Shōgun tells us just enough, itself an Eightfold Fence composed of dualities. Rather than Toranaga admitting his heart’s secret desire, he and Yabushige exchange smiles. Buntaro (Shinnosuke Abe), helps Blackthorne retrieve the Erasmus without the men exchanging a word. Likewise, the final onscreen look Blackthorne and Toranaga share is a moment of silent understanding. Conclusively knowing everything isn’t Shōgun‘s point, and neither is the heightened excitement of battle. Taking preventative measures, and ensuring the best landscape for future generations, is the goal. Whether it’s un-sinking the Erasmus‘s remains or preventing civil war, Shōgun sees people unite in a seemingly impossible task. They defy, re-direct, or surrender to a larger fate; a broadened perspective.

‘Shōgun’ Dreams About Peace

FX likely had the resources to depict a gore-filled Battle of Sekigahara, an event author James Clavell also left off his novel’s pages. Instead, Justin Marks and Rachel Kondo follow Clavell’s spirit and fortify their own creative instincts. Shōgun is about a world constantly on the verge of war and the complex people inhabiting said world, both those who facilitate endless death and those defying injustice. War is a curse men perpetuate. It’s something to dread, not glorify. The characters who survive Shōgun learn acceptance, selflessness, and honor instead of choosing that other well-trodden path.

Arriving at Shōgun‘s quiet, sensitive, and tranquil ending is like exhaling a long-held breath. Bodies still litter the journey, but their sacrifices held back a greater tragedy. As Blackthorne says, “It’s a shame that time [of lasting civility between enemies] will never come.” But as Shōgun, a triumph of the television medium, exists stage right, it holds on the image of a man staring ahead. He overlooks calm, still waters. In this rare moment, the dream of peace lives, facilitated by the courage of those who didn’t survive to see it.

Shōgun is available to stream on Hulu in the U.S.