Nashville, Tennessee – December 3, 2025 – Beneath the unyielding twang of a steel guitar and the relentless pulse of a Nashville heartbeat, Keith Urban has always been more than a performer—he’s a survivor, a storyteller whose every chord carries the weight of unspoken scars. For decades, the narrative around the New Zealand-born, Australia-raised crooner has been a tidy fairy tale: a wide-eyed kid under endless outback skies, strumming his first guitar by age six, inevitably drawn to country’s wide-open plains like a moth to a porch light. Fans and critics alike have spun it as destiny’s gentle nudge—a boy from the bush, influenced by Slim Dusty tapes and Johnny Cash concerts, who hopped a plane to Music City in his twenties and never looked back. But in a revelation that’s rippling through the industry like a rogue wave, Urban is finally dismantling that myth. In a series of intimate sit-downs tied to his just-dropped album HIGH—a 17-track odyssey of eclectic highs and heartfelt lows—the 58-year-old Grammy titan lays bare the unpolished truth: Country music wasn’t a choice born of geography or genre loyalty. It was survival. A lifeline thrown into the chaos of a fractured childhood, a turbulent adolescence, and a young adulthood teetering on self-destruction. “I wasn’t chasing fame or fitting into some mold,” Urban confesses, his voice a gravelly murmur over the hum of a late-night Nashville studio. “Country was the only place that let me bleed without apology—the only thing that made sense when nothing else did.” This isn’t PR gloss or holiday-season sentiment; it’s a reckoning, one that reframes his catalog—from “Somebody Like You” to “The Fighter”—as chapters in a hard-fought redemption arc. Once you hear it, you’ll never spin one of his records the same way again.

To grasp the depth of Urban’s disclosure, you have to burrow back to the red-dirt roots where it all took seed. Born Keith Lionel Urban (originally Urbahn) on October 26, 1967, in the sleepy coastal town of Whangārei, New Zealand, he was the second son of Bob and Marienne Urban, a couple whose immigrant grit masked a simmering storm. Bob, a Scottish-German mechanic with a penchant for American muscle cars and a hair-trigger temper fueled by alcohol, uprooted the family to Caboolture, Queensland, Australia, when Keith was just two. There, amid the subtropical sprawl of eucalyptus groves and endless horizons, the Urbans scraped by running a modest convenience store—shelves stocked with Tim Tams and tinned Spam, the till ringing out like a metronome to their modest dreams. Music, though, was the family’s fragile glue. Bob, a devotee of the American country sound that crackled over shortwave radios, blasted cassettes of Hank Williams and George Jones from the shop’s ancient stereo, his voice joining in on choruses with a fervor that bordered on fervent escape. “Dad lived for those songs,” Urban recalls in a recent Rolling Stone Country deep-dive. “They were his armor against the world—the one place he could feel big and unbroken.” For a boy absorbing it all from the shop’s backroom, those melodies weren’t mere entertainment; they were a portal, a way to navigate the shadows creeping at home’s edges.

The cracks widened early. Bob’s alcoholism wasn’t the cartoonish binge of barroom ballads; it was a quiet venom, manifesting in rages that left young Keith cowering behind the counter. “He’d hit me if I stepped wrong—nothing brutal like you’d read in headlines, but enough to make you small,” Urban shares, his eyes distant as if tracing old bruises. Physical discipline was the era’s grim norm in rural Australia, but for Keith, it etched deeper lines: a gnawing insecurity, a fear of volatility that mirrored the unpredictable squalls rolling off Moreton Bay. Music became his mutiny. At four, a ukulele appeared under the Christmas tree—a cheap import from Bob’s American obsession—and by six, a guitar teacher bartered lessons for store-window flyers. Those half-hour sessions in a dusty hall, fingers blistering on steel strings, weren’t play; they were defiance. “I’d hide in the shed after Dad’s storms, picking out chords until my hands bled,” Urban admits. “Country let me scream without words—turn the hurt into something that hummed back.” Slim Dusty, Australia’s godfather of bush ballads, loomed large: family pilgrimages to Tamworth’s Golden Guitar Festival in ’73, where Keith, at five, caught Johnny Cash live at Brisbane’s Festival Hall. The Man in Black’s gravelly gospel—”Folsom Prison Blues” thundering like judgment day—hit like lightning. “Johnny wasn’t just singing; he was surviving out loud,” Urban says. “That night, I knew: this music holds the broken pieces together.”

Adolescence amplified the ache. As a teen in the punk-fueled pubs of Brisbane, Keith gigged with bands like the Ranch—a rowdy outfit blending rockabilly riffs with country swing—while dodging Bob’s escalating demons. The store faltered, debts mounted, and alcohol’s grip tightened, turning home into a minefield. Keith’s own rebellions brewed: early experiments with substances, a restless itch to flee the familiar. Yet country clung like kudzu. It was broad enough for his rock edges—echoes of AC/DC’s Angus Young in his fretboard fury—yet intimate enough for confession. “Pop felt too shiny, rock too aggressive,” he reflects. “Country? It let you be messy—pour the wounds into a well and pull up something that healed.” By 21, rejection stung: a Tamworth audition flop, where judges dismissed his “too poppy” sound. Undeterred, he scraped visas and savings for Nashville in 1992, landing as a session gun-for-hire—strumming for Brooks & Dunn, the Dixie Chicks (pre-Chicks), and anyone with a demo budget. “I was invisible, crashing on couches, wondering if I’d gambled wrong,” he says. But the city’s alchemy worked: Capitol Nashville signed him in ’91 for an Aussie-only debut, Keith Urban in the US flopping stateside but planting seeds. His self-titled American breakthrough in ’99—”It’s a Love Thing” cracking radio—proved the gamble gold.

Yet survival’s sharper edge waited in the wings. Nashville’s siren call masked deeper tempests: cocaine’s cold grip in the early 2000s, a spiral that nearly derailed Golden Road‘s rocket ride (six No. 1s, including “Somebody Like You”). “I was chasing the high of connection, but it hollowed me out,” Urban reveals, echoing his 2016 Rolling Stone candor. Rehab in 2006—mere months after marrying Nicole Kidman in a Sydney ceremony that blended Hollywood glamour with Aussie grit—became his crossroads. Kidman, the poised powerhouse who’d weathered her own losses, stood sentinel: “She saw the man I could be, not the mess I was,” he says. Sobriety rebuilt him, but country was the scaffold—its storytelling a therapy session in three minutes. Tracks like “Wasted Time” from Be Here (2004) weren’t hits; they were hymns, exorcising the excess. “Country demands truth,” Urban insists. “You can’t fake the ache—it finds you out.” His sound evolved: Defying Gravity (2009) nodding to pop’s polish, Fuse (2013) fusing electronica edges, yet always anchored in narrative’s raw nerve. Collaborations bloomed—Carrie Underwood on “The Fighter,” Julia Michaels on Graffiti U—each a bridge from isolation to communion.

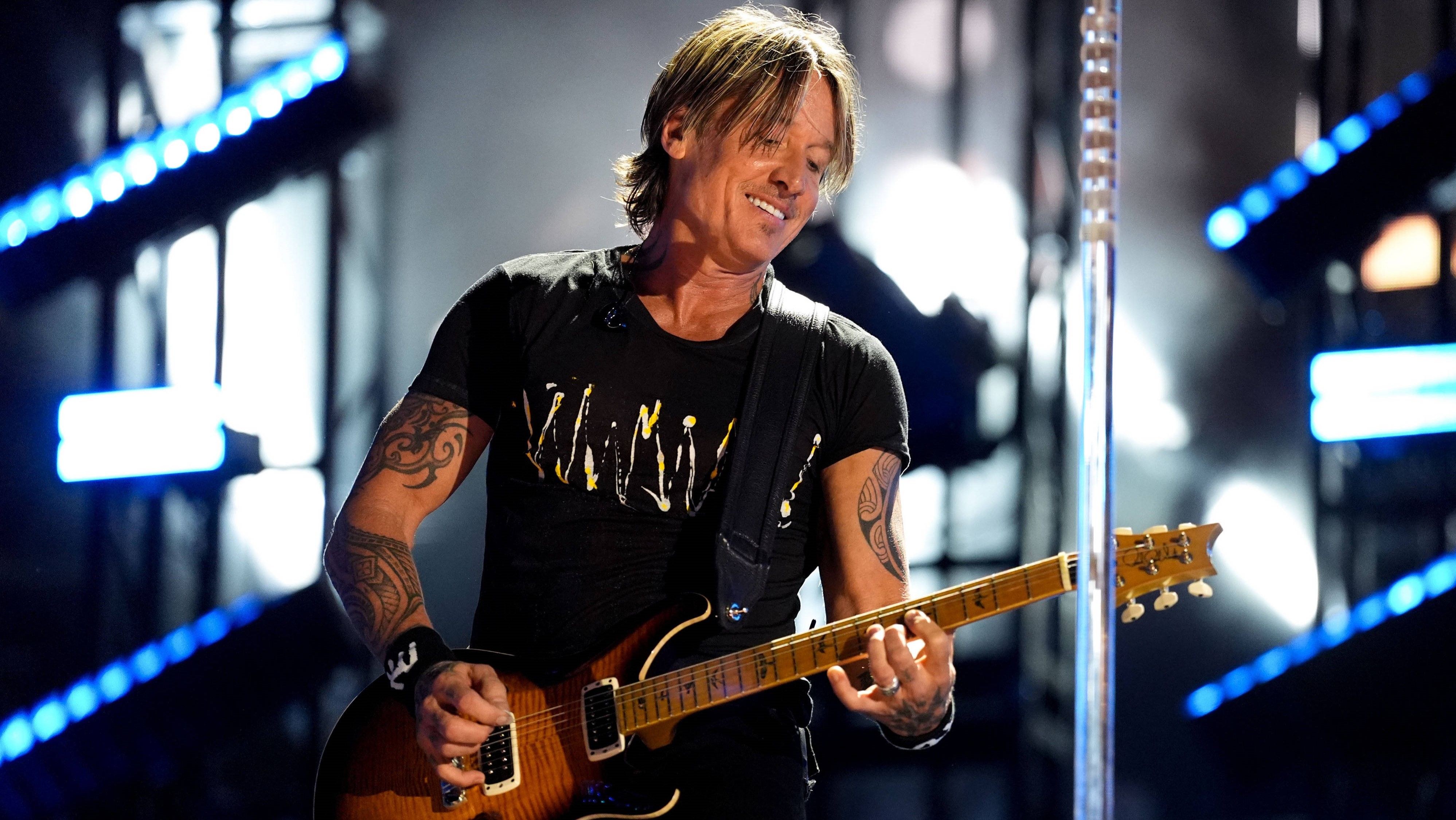

HIGH, his 2024 triumph (No. 1 debut, 17 tracks of genre-defying delight), crystallizes this catharsis. The closer, “Break the Chain,” is his starkest self-portrait: “Too late? Is it too late for me to listen, for me to change?” Penned with Marc Scibilia amid lockdown reflections, it’s a meditation on legacy’s ledger—discarding a father’s shadows while honoring the light. “We don’t pick our origins,” Urban says, voice steady but eyes wet. “Dad gave me the music bug, but also the blueprint for breaking cycles. Country let me rewrite it—not erase, but evolve.” The album’s sprawl mirrors his soul: reggae-tinged “Wildside” channeling youthful wanderlust, the title track a euphoric exhale of sobriety’s clarity. Fans, devouring it at 250 million streams, sense the shift—X threads buzzing with “Keith’s finally free,” TikToks syncing “Break the Chain” to recovery montages. At 58, married nearly two decades to Kidman (daughters Sunday Rose, 16, and Faith Margaret, 14, his “sunshine anchors”), Urban’s no longer the gypsy; he’s the guide. His 2025 tour—50 dates from Sydney Opera House to Madison Square Garden—feels like full-circle: the boy who strummed in sheds now lifts legions.

Urban’s unfiltered unburdening isn’t timely accident; it’s therapeutic timing. Amid country’s crossroads—crossover kings like Post Malone blurring borders, purists guarding the gates—his story reaffirms the genre’s core: resilience wrapped in rhythm. “I was born for this—not the lights, but the lift,” he says, strumming idly in a sun-dappled Nashville café. “Country saved me by letting me save others—one scar-shared song at a time.” It’s not glamorous, no red-carpet sheen. But in its grit? Profound power. Listeners, from Aussie outback faithful to Tennessee transplants, report refrains hitting harder: “Long Hot Summer” now echoes boyhood burns, “God Whispered Your Name” a sobriety psalm. As HIGH hurtles toward Grammy gold (nods for Album and Song), Urban’s revelation resonates: success isn’t arrival—it’s authenticity.

In a town built on tall tales, Keith Urban’s truth cuts deepest. Country wasn’t his fallback; it was his forge, hammering chaos into chords that endure. “Pour every wound into it,” he advises young strummers. “The music will hold you—and maybe heal someone else.” From Whangārei whispers to worldwide whoops, Urban’s odyssey proves: the best stories aren’t scripted. They’re survived. And in his hands, that survival sings eternal.