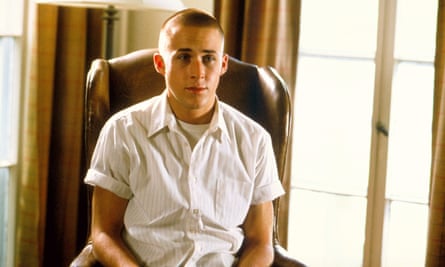

‘What Ryan has is a lack of insecurity about teasing himself, his stardom and his masculinity.’ Composite: Guardian Design; Album; Kobal; Allstar; Shutterstock; Warner Bros; Entertainment Pictures; Alamy

Evolution of man: how Ryan Gosling changed stardom, cinema and society

This article is more than 2 months old

The actor’s feminist credentials, a wholehearted embrace of comedy and being one of the most memed actors on social media has seen Gosling’s auto-satirising alpha male become white-hot box office in 2024

In Hollywood, there are no accidents. Ryan Gosling’s role in stuntman pic The Fall Guy, hard on the heels of his show-stopping Oscars rendition of I’m Just Ken, is perfectly timed to confirm his ascension to the very top tier of stardom. Not only is it a four-quadrant entertainment turbo boost – covering all audience bases with action, romance, a legacy franchise for the oldies, John Wick-slick for the kids – it is shrink-wrapped to his public persona. His role as stunt veteran Colt Seavers, saving the skin of the idiot megastar he doubles for, caps off the stance Gosling has upheld on talkshows and memes over the last decade: stardom and celebrity as a delectable facade, an in-joke between star and audience to be played with the lightest of ironic touches.

But of course Gosling is a bona fide star, one of Hollywood’s most important. His confused, toxic himbo Ken stole the Barbie limelight from Margot Robbie. Tunnelling into classic archetypes of masculinity with modern self-awareness is the on-screen niche he has made his own – giving us a new, uniquely supple male star for the post-#MeToo era. His mainstream roles – getaway drivers, daredevil motorcyclists, venal bankers – have often been ultra-macho, but the actor himself comes with rounded metrosexual edges. Men want to be him, with his debonair cool and inexhaustible supply of swanky jackets (the leather Miami Vice stunt-team number in The Fall Guy being the latest). As far back as 2017, Morwenna Ferrier noted that Gosling clones, sporting a certain “turbo cleanliness”, were now on the loose in cities everywhere.

At the same time, this role model status doesn’t alienate women; in fact, like most well-adjusted male stars in this day and age, he wears his feminist credentials on his perfectly pressed sleeve. Raised by his mother and older sister, he said in 2016: “I think women are better than men. They are stronger, more evolved.” A year later, accepting his Golden Globe for La La Land, he thanked his “lady”, Eva Mendes, for raising their daughters while he was on set. When Robbie and Barbie director Greta Gerwig were overlooked at this year’s Globes, he objected in writing: “There is no Ken without Barbie.”

And crucially his best work services both sexes, often putting him in subordinate roles that like Ken are candid about male frailties. His Officer K in Denis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner sequel looks, like any self-respecting replicant-hunter, like a Raymond Chandler gumshoe. But he is a patsy swept along on narcissistic, all too 21st-century delusions of specialness. (The internet got the hint, memeing his self-righteous “Goddamnit” outburst.)

The Fall Guy is more relaxed – but still self-deprecating. With his biceps and blond feather-cut, driving, fighting, falling human multitool Seavers is cut from heart-throb cloth. But he wears this burden like his battered jacket. “I never saw a fist I didn’t remember,” he says after a pummelling. The film’s screenwriter Drew Pearce confirms that Gosling’s adeptness at playing two ends of the spectrum was key to the film: “He’s both authentically masculine, yet also emotionally vulnerable. It’s the best of an old-fashioned movie star like Steve McQueen, with a modern twist of sensitivity. In the movie we play with that dichotomy – his character is a good guy, for sure, but there’s a blind spot in his emotional self-awareness that comes from a very masculine place.”

Undercutting machismo is nothing new, of course: that was the USP of the emerging male stars of 90s New Man-era Hollywood, such as Keanu Reeves, Johnny Depp and Leonardo DiCaprio. But Gosling’s ability to simultaneously affirm and question masculine mores, in films at the very top of his profession, does feel new. His Barbie press tour – lamenting his daughters’ indifference to their Ken dolls, while running with a Kenucopia of terrible puns – was a work of art. This was a man obviously drawing from a deep well of misplaced gender expectations: after being fired up by a childhood viewing of Sylvester Stallone in First Blood, he was suspended from school after lobbing steak knives at fellow pupils. Sly’s habit of wearing minks while directing apparently inspired Ken’s wardrobe.

Gosling’s emergence as auto-satirising alpha male is all the more fascinating for the long time it has taken. Not an especial singing or dancing talent, he wasn’t on the same 90s fast track as fellow Mouseketeers Britney Spears, Justin Timberlake and Christina Aguilera. It was 10 more years until his first notable box office success in 2004 weepie The Notebook, his own balsa-wood Titanic. Cast by director Nick Cassavetes for having “no natural leading man qualities”, he was an engrossing mess opposite his love rival, the more conventionally luscious James Marsden. In contrast with his current GQ spiffiness, there was something gawky about the long-chinned actor during this period. But his subversive glint saw him in good stead during the string of riveting misfits he played in the 00s: a self-hating Jewish neo-Nazi in 2001’s The Believer, a crack-addicted high-school teacher in 2006’s Half Nelson, and a somehow-endearing sex-doll enthusiast in 2007’s Lars and the Real Girl.

His long showbiz gestation – and being arguably the most memed actor of the social media age – means Gosling feels closer to being one of our own than the typical Hollywood star; a closeness exploited by The Fall Guy in making him the audience proxy, next to airhead megastar Tom Ryder, played by Aaron Taylor-Johnson. Growing up aware of how the industry propagates gender standards, he’s earned his stripes in terms of later making these norms malleable. The damaged complexity of his indie phase persisted in Gosling’s take on masculinity once he was at Hollywood’s high table: the diminished, decentralised and incompetent men of The Nice Guys, Blade Runner 2049, and Barbie.

But occasionally he has almost seemed to enjoy succumbing to mainstream industry “nihilism”, as Seavers skewers the oeuvre of Tom Ryder. Gosling’s monosyllabic getaway man in Nicolas Winding Refn’s head-stomping fairytale Drive was, in the actor’s words: “a guy that’s seen too many movies”. He returned to the same caricatural taciturn action mode – sporting a toothpick once again – in the recent Netflix movie The Gray Man.

It seems trite to point out the quality now obvious to everyone, but embracing comedy is what really put Gosling in the mainstream. Playing a Neil Strauss-type pickup artist with an unfeasible abdomen in 2011’s Crazy, Stupid, Love was his first wholehearted stab at the genre, though his facility with larkiness was there in his uxorious wiseguy in Blue Valentine the year before. According to the leaked Sony emails, he was still actively canvassing in that direction in a 2014 meeting with studio head Amy Pascal. Crazy, Stupid, Love also cemented him in the zeitgeist as the arch-smoothie of the Hey Girl meme doing the rounds during that period; something he seemed happy to endorse (ironically).

The high camp of his recent Oscars performance – the Gentlemen Prefer Blondes aesthetics, tittering as he chin-bumped Mark Ronson – was the fuchsia icing on the cake of his insouciant approach to fame. “I have a theory about leading men,” says Pearce. “They really transcend and become an all-timer the moment they realise that the goofier they are – the more they throw away what other people hold on to, the ‘trying to be cool’ part – then they become something more cool. What Ryan has is a lack of insecurity about teasing himself – about his stardom, his masculinity.”

Paul Newman, and his “ironic sensibility” in the likes of 1966 detective pic Harper, is the classic-era equivalent Pearce had in mind while writing The Fall Guy. But Gosling is even more stylised in his comedy outings: he is a straight man by trade, and often even a stooge. In Barbie, the joke – even in his equine-based embrace of the patriarchy – is always on Ken. Gosling’s old-lady-swindling PI in 2016’s The Nice Guys spends as much time dropping cigarettes down his pants, injuring himself when breaking and entering and irresponsibly parenting as turning up viable leads. A certain underlying tetchiness, allied with his dusty voice, make the actor a natural for this deadpan work. He kills his scenes as credit default swap king Jared Vennett in The Big Short, reeling off predatory financial advice with an unrepentant straight face. His timing and tone are invariably superb. Only Gosling, in an SNL skit, could make a crusade against a bad font play like All the President’s Men.

It’s curious to see something as old-school as a straight man become white-hot box office in 2024. And it’s undoubtedly a boon for cinema in its current turbulent and panicked state; it can still spawn blockbusters with enough heat to ignite new stars. It’s not clear if the likes of Timothée Chalamet, Zendaya and Sydney Sweeney are capable of that feat of old: launching a film on their names alone. But Robbie and the veteran Gosling feel closer to possessing that kind of firepower – probably not enough to “save” cinema, but at least to give us hope that it is not in terminal decline.

Gosling’s drawn-out, teasing shimmy to the top and tight rapport with audiences gives him added credibility as a headliner. His appeal is sophisticated: his style connects him back to retro masculine archetypes, but with a modern veneer. That throwback musical La La Land – with him holding out for jazz (“It’s dying – but not on my watch”) and old-timey romance – located the sweet spot between the two. Of course, he later sent it up on SNL.

But how far can that perfectly calibrated irony take him? If the shtick congeals, he might be a new Roger Moore in waiting. And is his enlightened brand of masculinity, hinting at a course correction for Hollywood gender relations, really meaningful – or just new packaging? But among the many abilities he has shown, Gosling knows how to evolve. To deepen his appeal and artistry, not to mention ticking awards-season boxes, he may have to seek out penetrating roles in straight drama – something, outside reteaming with La La Land director Damien Chazelle in Neil Armstrong biopic First Man, he’s hardly been seen in over the last decade. But for now, the Ryanaissance can wait; he’s the Gosling that’s laying the golden eggs.