The Walking Dead is bigger—and slower—than it’s ever been. Sure, the series hit the narrative doldrums in Season Two, in what felt like a bout of needless wheel spinning, but those kinks seemed to have been ironed out in the time since. There’s a reason the series is one the decade’s biggest hits, and it’s because it’s (mostly) been pretty darn good. Then Season Seven came along. With Negan’s skull-bashing cliffhanger hanging over its head, The Walking Dead returned riding a mountain of hype, and to this point it’s had trouble delivering.

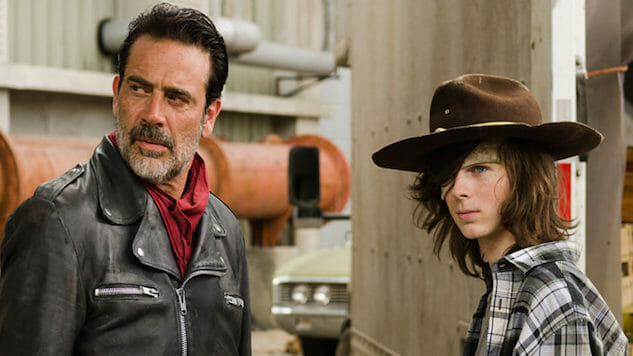

Ever since the Governor bit the dust a few years ago, fans of the series have been waiting with bated breath to meet the comic villain who made the eye-patched mayor of Woodbury look like a teddy bear. Negan is one of the most popular characters to come from the comic canon, and with the blockbuster casting of Jeffrey Dean Morgan in the role (arguably the most well-known actor the cast of relative unknowns has attracted to date), you knew AMC was going to milk it for all it’s worth. Which didn’t necessarily have to be a bad thing. But with Sunday’s midseason finale upon us, it’s become clear that The Walking Dead is content to keep kicking dirt around the sandbox it’s created, instead of moving on to new terrain. Rather, it’s starting to feel like the AMC series’ creative team would prefer to play with the shiny, new Jeffrey Dean Morgan action figure they just pulled out of the box, Lucille and leather jacket included. The Walking Dead has never been the fastest-paced series on TV, but it once possessed a certain narrative energy—which is saying something, especially for a series whose premise is basically that it’s an endless apocalypse.

Much of that prior success can be traced back to Robert Kirkman’s immensely successful comics (still going, by the way), which the series has mined again and again for key story elements, sometimes panel by panel. Yes, the TV series has taken some liberties along the way (Andrea is dead, Carol is alive and awesome, Daryl exists, etc.), but they’ve largely kept the bones of Kirkman’s story in place. Which makes the frustratingly slow start to Season Seven all the more, well, frustrating. The framework is there, and they’re actually following it, for the most part—they just need to do it with more urgency. Considering that Kirkman’s been telling this story for 13 years and 160 issues (and counting), there are still seasons’ worth of material from the comics to adapt, and more being written with each new issue. So why spend eight episodes—several of them super-sized—meandering around the realization that Negan is a Really Bad Dude?

Put simply, there is no reason. We’re at the midseason break, and you could’ve skipped all but one or two episodes and not missed much. That’s not a good thing. And looking to the comics, that seems to be something Kirkman already knows.

The season-long wait for Glenn’s death? Kirkman wrapped it all up in issue 100, no cliffhanger required. The TV series is now focusing on elements from issues 104-105 of the comic at this point—the “What Comes After” arc. Carl’s failed attack on Negan is right out of the comics, and at least in that version of the story, it’s the start of a bizarre friendship between the two. We start to see the seeds of that planted on screen, as well. Which is fine! It’s a good story in the comics, and might well work in the series. But where the comic is limited by a page count each week, AMC’s adaptation has begun to stretch the hour-long drama to its breaking point: Without the need to be concise, the TV series no longer has the impetus to focus on its strongest, most important narrative threads. Not every scene needs to make it on screen, after all. There’s a reason most footage ends up on the cutting room floor.

Despite a ratings slide this season, The Walking Dead remains one of the most-watched series on television, and unfortunately AMC has decided to milk that status for all the ad dollars it’s worth—to the point of adding more “expanded” episodes (and by extension more commercial breaks) with each season. Surprise, surprise: It turns out padding an already slow story with 10 or 20 extra minutes isn’t really the answer.

In the comics, the Carl/Negan subplot plays out over three issues (104-106), but it’s important to note there are several other plotlines moving forward around it. On the TV series this season, by contrast, plot points appear as if they’re happening in a vacuum—a way for the writers to bide their time before bringing these disparate stories (i.e. The Kingdom, Tara’s beach colony) together down the line. The problem is, there’s no momentum to suggest that moment is drawing any closer.

Again, by this point in the comics, one-handed Rick has already made it clear he’s working toward a plan to oppose the Saviors and usurp Negan. Everything that happens has weight, presaging the eventual face-off (the “March to War” and “All Out War” arcs), whereas the first half of The Walking Dead’s seventh season has lacked that narrative thrust. It may have been compelling, at first, to see Rick floundering, but he’s been floundering for seven episodes now. It’s time he starts to at look beyond the next scavenging run for the Saviors. (It’s possible, I suppose, that he’s been working an angle ever since Glenn died, but if so, it’s long past time for the writers to let the audience in on that fact.)

For a series that’s been slow to widen its world, this season has opened a window on not one but two brand new communities. That’s a potential mountain of new material, new relationships, new characters and new locations to explore, and yet we’ve been submitted to one after another of Negan’s trips to Alexandria, where he’s once again rude to women and menacing around town. (Negan has always worked best in small doses.) For a comic to run for 13 years with no wholesale change in creative direction is practically unheard of these days, but by continuing to push its narrative to new places, The Walking Dead comics get better with each installment. If the TV series doesn’t start to take a page or two from that book, and soon, it seems destined to move in the opposite direction.