For anyone concerned about performance-based compensation going away because it’s no longer tax deductible, have no fear. Elon Musk is here to save the day (again).

As the CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, Musk is a pioneer in the automotive and space travel industries. Turns out his innovative spirit extends to his own compensation as well, based on a new pay package announced last week.

According to an SEC filing from the company, Musk will be eligible to receive a 10-year performance option grant—pending shareholder approval—that ties his compensation potential entirely to meeting a combination of company performance and market cap goals. The plan has been well-covered, even called “the boldest pay plan in corporate history” by The New York Times, so we won’t go into much more detail in this blog, and rather look at the implications with respect to the larger executive compensation picture. (Read the entire 68-page plan outline here.)

The fact that Musk’s pay is tied to performance goals is not unusual. Indeed, executive compensation has been trending this way since the recession, Dodd-Frank and Say on Pay. What is unusual about Musk’s award is that his compensation is entirely reliant on meeting aggressive goals both for Tesla’s success and for shareholder value, otherwise he doesn’t get a dime (or a share, as the case may be).

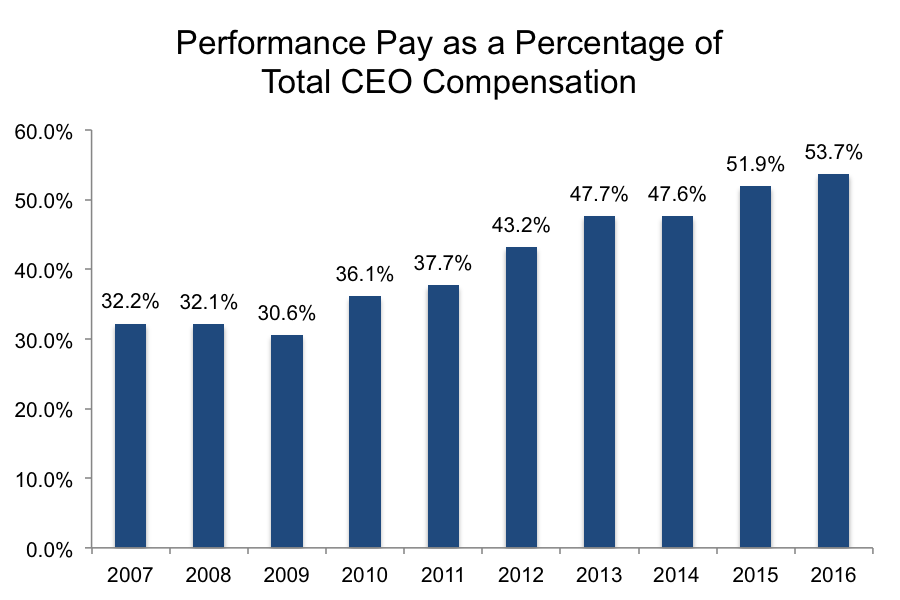

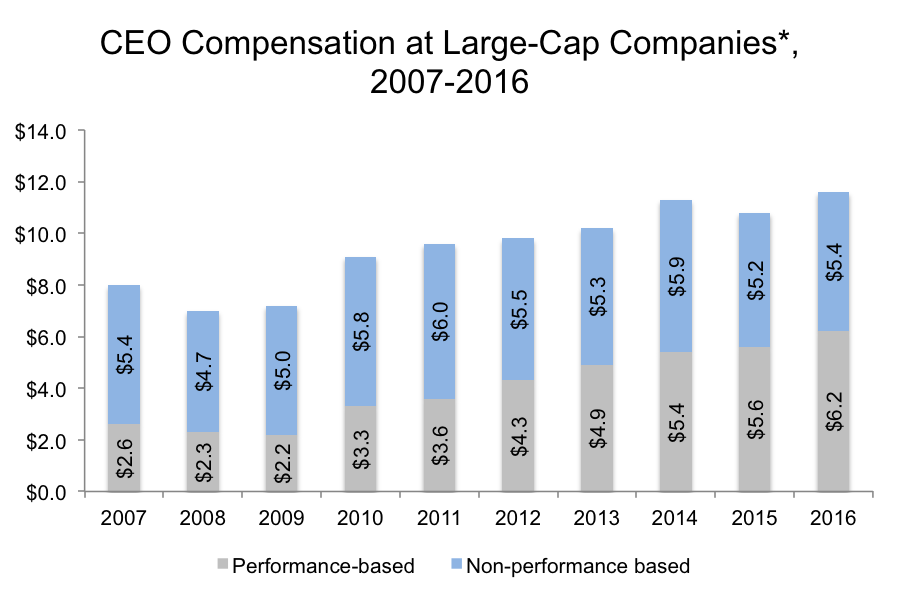

To put Musk’s package in perspective, Equilar examined performance pay trends over the last 10 years. Indeed, the shift to performance pay is being felt across large-cap companies*, and this is unlikely to abate. In 2007, median CEO compensation tied to performance accounted for 32.2% of median reported pay in the summary compensation table (SCT). By 2016, that figure increased to 53.7%. The charts below show the trend line for performance as a share of total compensation, as well as the absolute median values for CEO pay in terms of performance-based vs. other fixed salary or time-based equity compensation.

As Equilar examined in a report penned in partnership with Fidelity Stock Plan Services (and featuring comments from Aon Equity Services), the new Tax Cuts and Jobs Act removed tax deductibility of performance-based executive compensation above $1 million. Some have speculated that this could lead to a reduction in variable compensation, and a shift to more fixed salary. In the days following the tax bill passing, Netflix announced that it would be shifting all of its executives’ variable cash bonuses into salary, prompting many to postulate on whether or not this would become common practice. That has so far been one of the only high-profile cases of this occurring, and compensation professionals don’t expect this shift to be a wide-reaching trend.

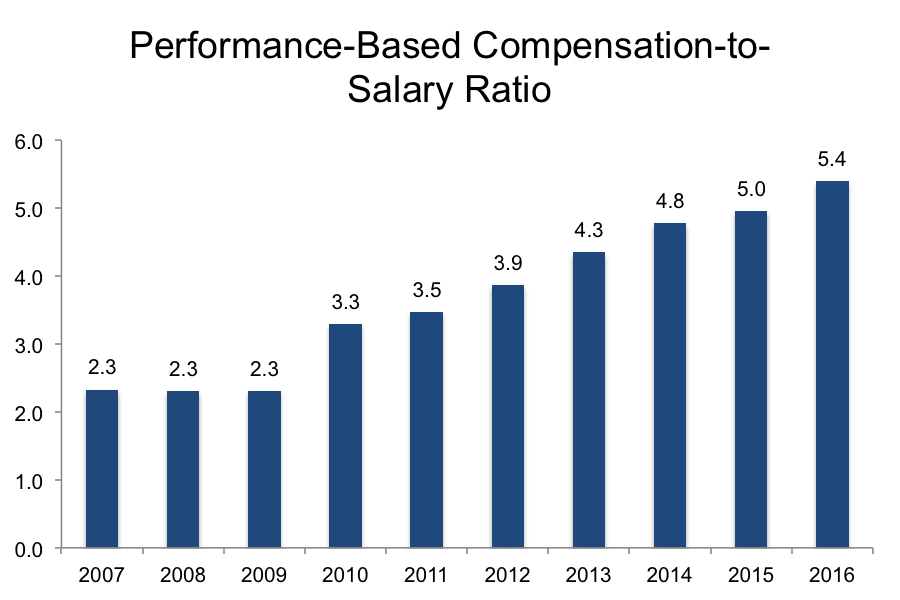

Over the past 10 years, performance-based pay has shifted to the point where it now outpaces salary more than five-to-one at the median for the same group of CEOs examined in the previous charts. This trend is part of the reason Netflix is not expected to lead a massive reversal in a market-wide evolution toward executive pay for performance.

Musk’s pay design is a quintessential example of how pay for performance is supposed to work. His option grant of up to about 20.3 million shares may be reported to the SEC as $2.6 billion in total compensation in the company’s 2019 proxy statement (pending shareholder approval). In addition, the company noted in its outline of the plan to shareholders that the plan has potential value of up to $55.8 billion—in the unlikely case of all things being equal from now in terms of total share count until all tranches are vested. But either way, the total value of this grant could turn out to be monstrous. Or, it could turn out to be zero. (The former is far more likely, even if the payout doesn’t reach it’s full value.)

There is criticism that companies stack the deck to meet performance goals, and therefore, this ostensibly variable pay is not so variable. On an individual company basis, that’s for shareholders to decide, as they will in Tesla’s case at a special shareholder meeting in March exclusively for the purpose of discussing Musk’s compensation.

While Tesla shareholders would be justified in having high confidence in Musk—after all, he achieved nine out of 10 performance and market cap milestones from a similarly structured 2012 grant—the new goals are far more aggressive. The company’s market cap grew from $4 billion to $59 billion from 2012 to now, and in order to receive the first tranche, the company would have nearly match that growth in order to reach $100 billion. To achieve the final market cap goal—$650 billion, Tesla has to find a way to scale exponentially. A bet against Musk may not be the wisest bet, but the odds are certainly long.

One could argue (appropriately) that Musk doesn’t need the money. And I would argue that this pay package is not about money. It’s about a signing a contract with shareholders to get on board with the rocket ship—bad pun about Musk’s other company intended—and if he can’t take them there, he won’t share in the wealth. While we shouldn’t expect to see another pay package exactly like this, it’s an extreme, but clear, example of why pay for performance is not a passing fad, and why it’s not likely to go away just because it’s not tax-deductible anymore.