It’s almost impressive how Amazon’s extraordinarily expensive series, now in its second season, amounts to so little.

Amazon Studios

The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power always had a tough act to follow. Drawing from one of the most revered novels of the 20th century—or, rather, 130 pages appended to it—and beholden to Peter Jackson’s film adaptation, Season 1 of the Amazon series met with a generally positive if wary response for its approach to the Second Age of Middle-earth. Now in its sophomore season, The Rings of Power is strangely placed. Where Jackson, and animator Ralph Bakshi before him, created a visual and tonal taxonomy that captured the spirit of J.R.R. Tolkien’s story and yet also felt unique, The Rings of Power has thus far struggled to reproduce the magic of what has come before, while also failing to carve out a space of its own.

Drawing from a host of oral tradition and mythmaking—particularly Old English, Germanic, and Scandinavian mythology—Tolkien spent decades developing his Middle-earth lore, lending The Lord of the Rings not just a rich history but a sense of familiarity. Whether it’s in the absurd heroism of the Táin Bó Cúailnge, the inset myths and histories of Beowulf, or the almost hackneyed high style of the Prose and Poetic Eddas, one can find echoes of a motive history that Tolkien fashioned to drive his characters. Borrowing from these sources, he built a world in which people, place, and past feel connected. Characters don’t just change; the world changes them and changes with them, as does the language around them. All this adds up to a genuine narrative depth.

It’s a broader tone that Jackson captured in the Lord of the Rings trilogy: that sweeping, operatic romance backed by a deep past. But although Tolkien brought a world of myth into his Middle-earth sagas, Jackson tapped into a history of visual media. Most apparent—especially watching The Fellowship of the Ring—is the influence of horror. Think of the Ringwraith edging toward the Hobbits as they cower beneath a tree root, Bilbo’s sudden transformation upon seeing the Ring again, and even the frequent jump-scare reveals of the Eye of Sauron throughout. If Jackson captured the high fantasy of The Lord of the Rings, he made it his own by heightening the horror that already simmered beneath each scene.

That identity feels all the more important as The Rings of Power is unable to grasp it. This isn’t necessarily a failing in and of itself; after all, we don’t require a rehashing of Jackson’s style for a successful addition to the Tolkien-verse. But the depth of emotion and motivation that Tolkien wrote, and that Jackson echoed, is notably lacking here. The history that drove Tolkien’s narrative and heightened Jackson’s dread is gone, taking the romantic heroism with it.

Go back to those classic myths and you’re assailed by a rousing absurdity as heroes contend with the gods, slay hundreds of foes without breaking a sweat, or hew whole forests in single strokes of an axe. Tolkien lets these ideas reverberate in moments like Théoden, King of Rohan, blowing a war horn with such gusto that it shatters; his niece Éowyn striking down the Witch-king of Angmar; or the Fellowship holding back a horde of goblins in Moria.* In contrast, The Rings of Power drags these more awesome moments into the ordinary. Gone is the operatic scope, the lofty heroism, and the sense of profound peril. Instead, we’re subjected to disappointingly tamer episodes like Isildur (Maxim Baldry) looking for his horse, past Sauron (Jack Lowden) being slime for a bit, or Galadriel (Morfydd Clark) continuing to be a bit horny for the Dark Lord (post-slime, Charlie Vickers). We get little sense that we’re watching something profound unfold, that these are mythic heroes—many of whom have already come through the great First Age battle known as the War of Wrath—who will one day overthrow Sauron. It doesn’t feel humanizing so much as shallow, taking the grand scope of The Lord of the Rings and explaining it into oblivion.

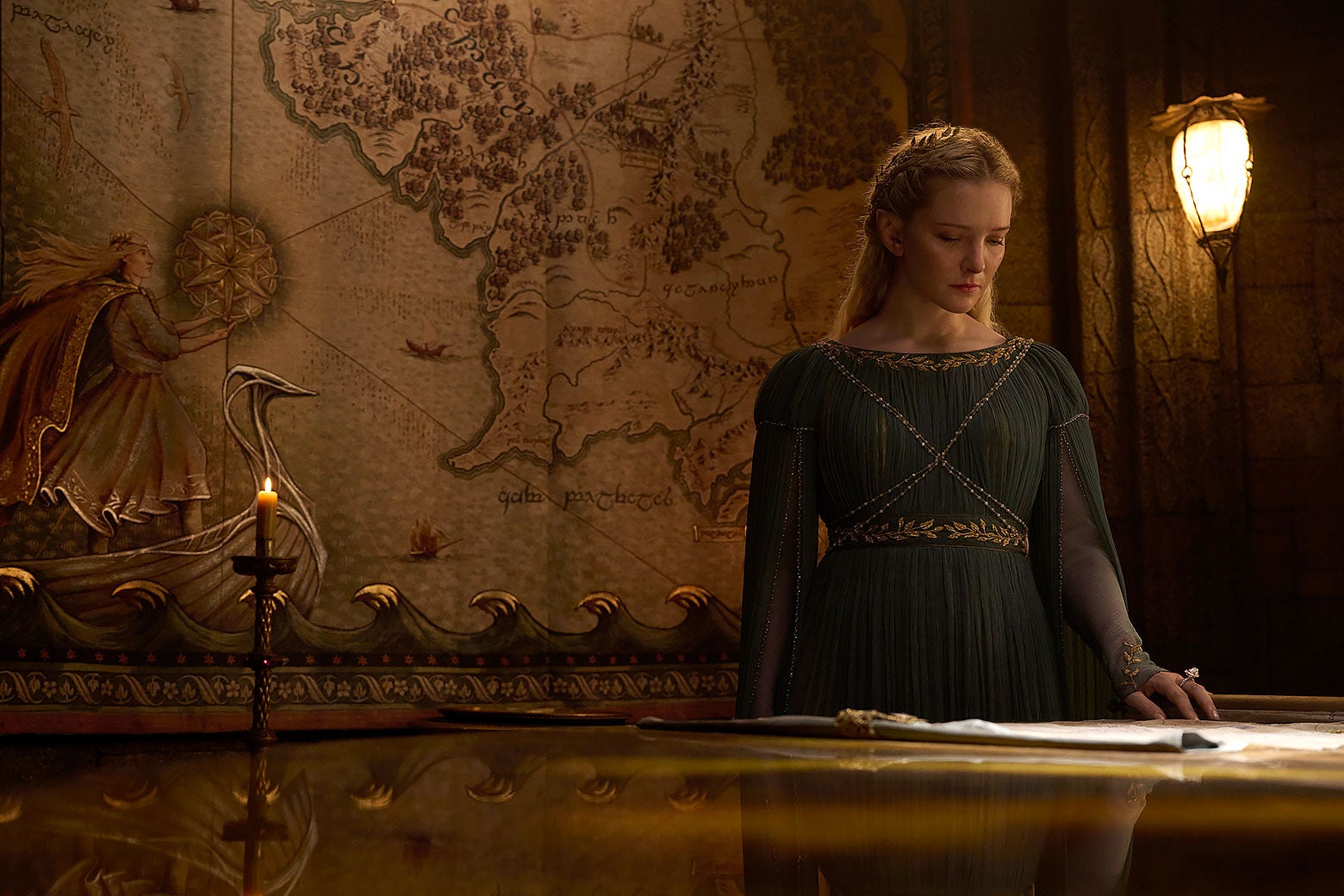

This is perhaps a symptom of having to fashion a series from a fraction of this specific history; Amazon does not have the rights to The Silmarillion, in which Tolkien elucidates the history of the Second Age in more detail. It’s worth noting, too, that for all its faults The Rings of Power remains an undeniably beautiful production. It’s a marvel of set design, costuming, and hair and makeup that echoes the craftwork that made Jackson’s cinematic world seem so real—and that felt so lacking in the rushed production of the Hobbit movies.

In lieu of being able to create a powerful story, it’s here that The Rings of Power might have salvaged a bit of depth through at least some environmental history and storytelling. Yet, although they’re gorgeous, don’t all those clothes feel very new? All that armor strangely clean? Contrast this with Aragorn’s ragged ranger gear in The Fellowship of the Ring, which communicates the long years Viggo Mortensen’s character has spent in the wilderness, and it becomes even harder to find a holistic cohesion in The Rings of Power that could even vaguely be construed as identity. The exquisite look of the series is arguably the best thing about it, but it simultaneously epitomizes how sanitized it feels compared with what has come before—how it seems less a sincere adaptation than the result of a streaming production line.

Perhaps the real test of The Rings of Power will be how it depicts the Siege of Eregion, which takes place at Celebrimbor’s (Charles Edwards) forge. Though a relatively short battle, this pivotal skirmish will be stretched over three episodes as a showpiece for Season 2. It’ll be curious to see how it compares, for instance, with the Battle of Dagorlad, where the Last Alliance led by Elendil and Gil-galad overthrew Sauron. In a few minutes in The Fellowship of the Ring, that battle felt profound and affecting for the broader narrative, yet one suspects that the Siege of Eregion will be much the same as the rest of The Rings of Power: elongated to near irrelevance or, as Bilbo says, “like butter scraped over too much bread.”

I have a lot of sympathy for those working hard on The Rings of Power. Forced to draw on a minuscule part of Tolkien’s world in The Lord of the Rings’ appendices, built from a limited vision of its showrunners, this extraordinarily expensive endeavor ultimately amounts to so little on-screen. Still, as much as The Rings of Power wants to be The Lord of the Rings, I can’t help but think it is in name only. I can’t shake the sensation that, as we compare it with what has come before—and sense that the temptation is to lump it in with Jackson’s Hobbit movies as lackluster adaptations—it cleaves far closer to Amazon’s similarly flat fantasy series The Wheel of Time than anything Tolkien created.

In that sense, the show has become less an adaptation of Tolkien than a vague reflection of The Lord of the Rings’ monumental influence on all fantasy that has followed it. The result is so generic, so devoid of history, that the enormous world of both Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and Jackson’s films has been made so small.