Looking back on his long-running zombie comic series in retrospect, The Walking Dead creator Robert Kirkman acknowledges that he might have resorted to one particular trope a little too frequently. That said, Kirkman’s liberal use of the “person-talks-to-inanimate-object” cliché can be defended for its artistic motivations, even if some examples from the series were more successful than others.

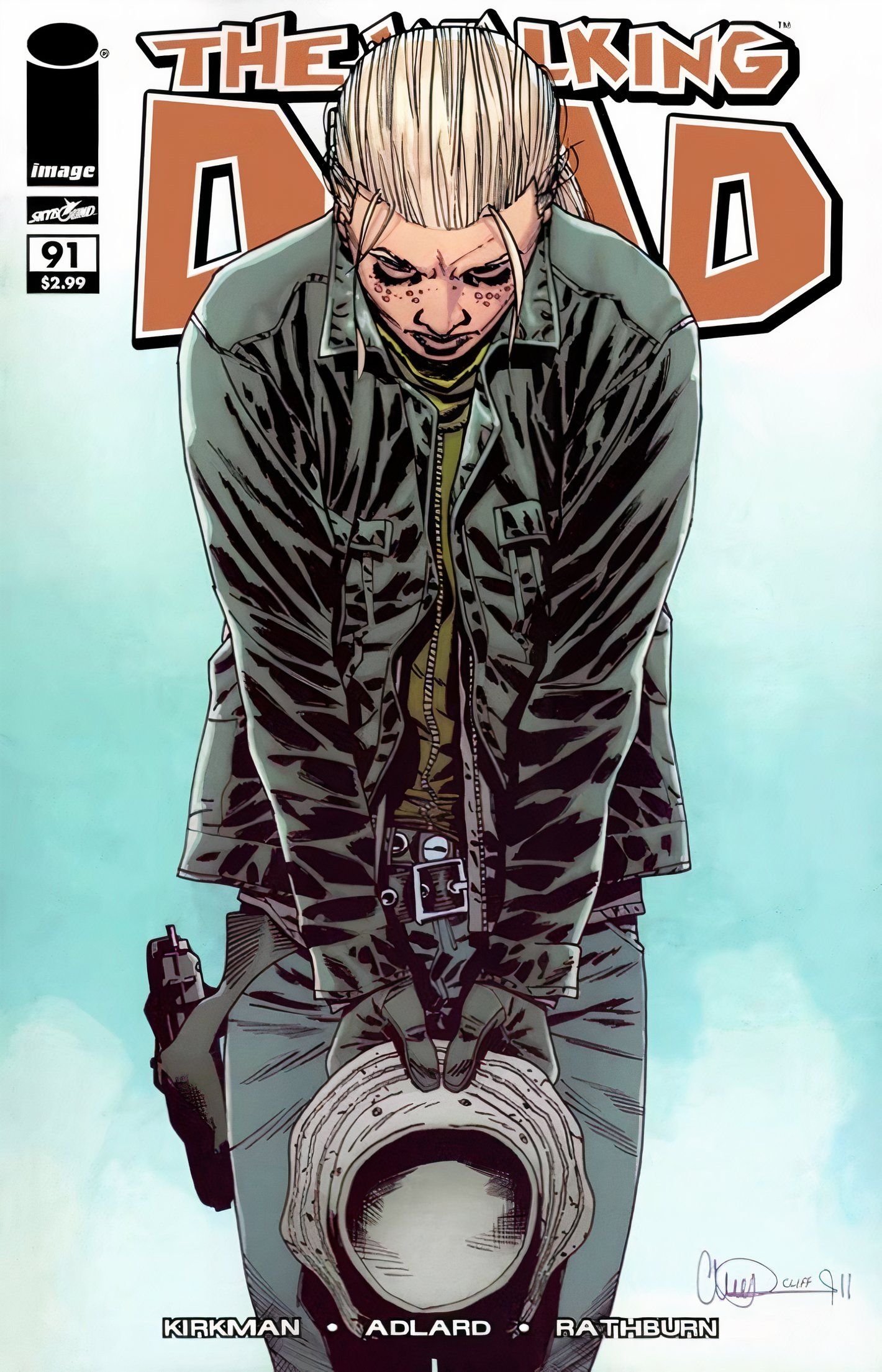

As has become the most exhilarating part of the reprint, The Walking Dead Deluxe #91 – written by Robert Kirkman, with art by Charlie Adlard, rendered in full color for the first time – features annotations from the author, reflecting on his career-defining opus. Kirkman has at times been notably critical of his work upon returnign to The Walking Dead; in this case, he gently chided himself for resorting to a particular narrative technique too often.

Despite admitting he “[got] what [he] was trying to do,” Kirkman asserted that he scripted too many one-sided dialogues, with characters talking to objects.

Robert Kirkman Calls Out His Use Of 1 Recurring Narrative Device

The Walking Dead Deluxe #91 – Written By Robert Kirkman; Art By Charlie Adlard; Color By Dave McCaig; Lettering By Rus Wooten

While these examples do exhibit a degradation of narrative effectiveness, it is arguable whether the trope can truly be said to have been overused.

As The Walking Dead’s author pointed out in The Walking Dead Deluxe #91, he repeatedly featured characters talking to objects in the comic. In every case, to some degree or another, this was a product of creative necessity – but as a more mature creator surveying his earlier work, the repetition of the device stood out to Robert Kirkman, who gently chastised himself. He wrote:

Robert, Robert, Robert…you got Michonne talking to a sword. Rick talking to a broken phone. Come on man…this is a bit much. Thankfully, I don’t think Andrea ever spoke to Dale’s hat again…and kind of, this scene is her saying it’s kind of stupid anyway. I get what I was trying to do, and it is emotional, but it’s a well I probably dipped in into far too often.

Kirkman himself points out that there was an authorial intention behind each instance of the trope, though the degree of effectiveness of each instance can be debated.

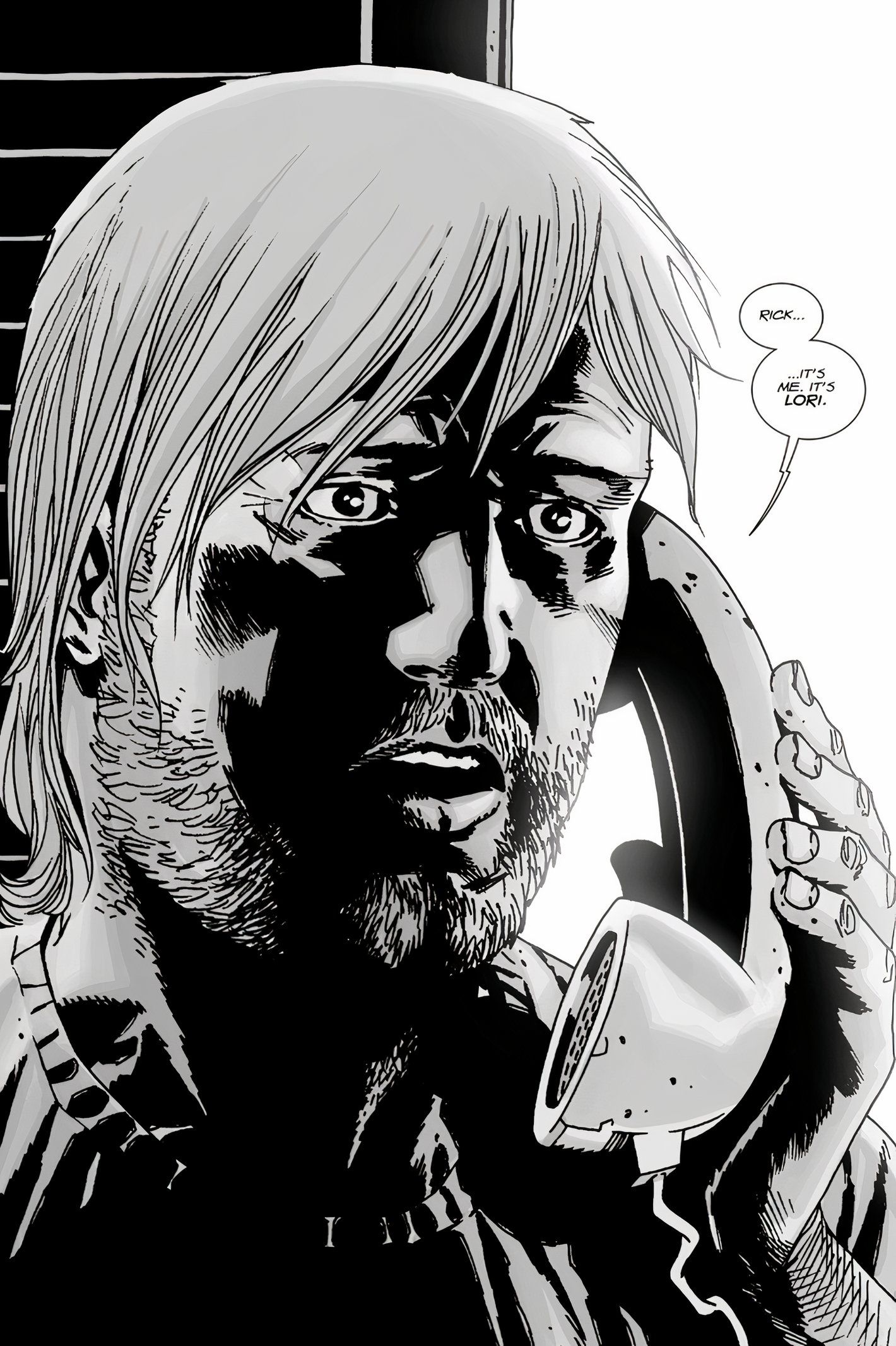

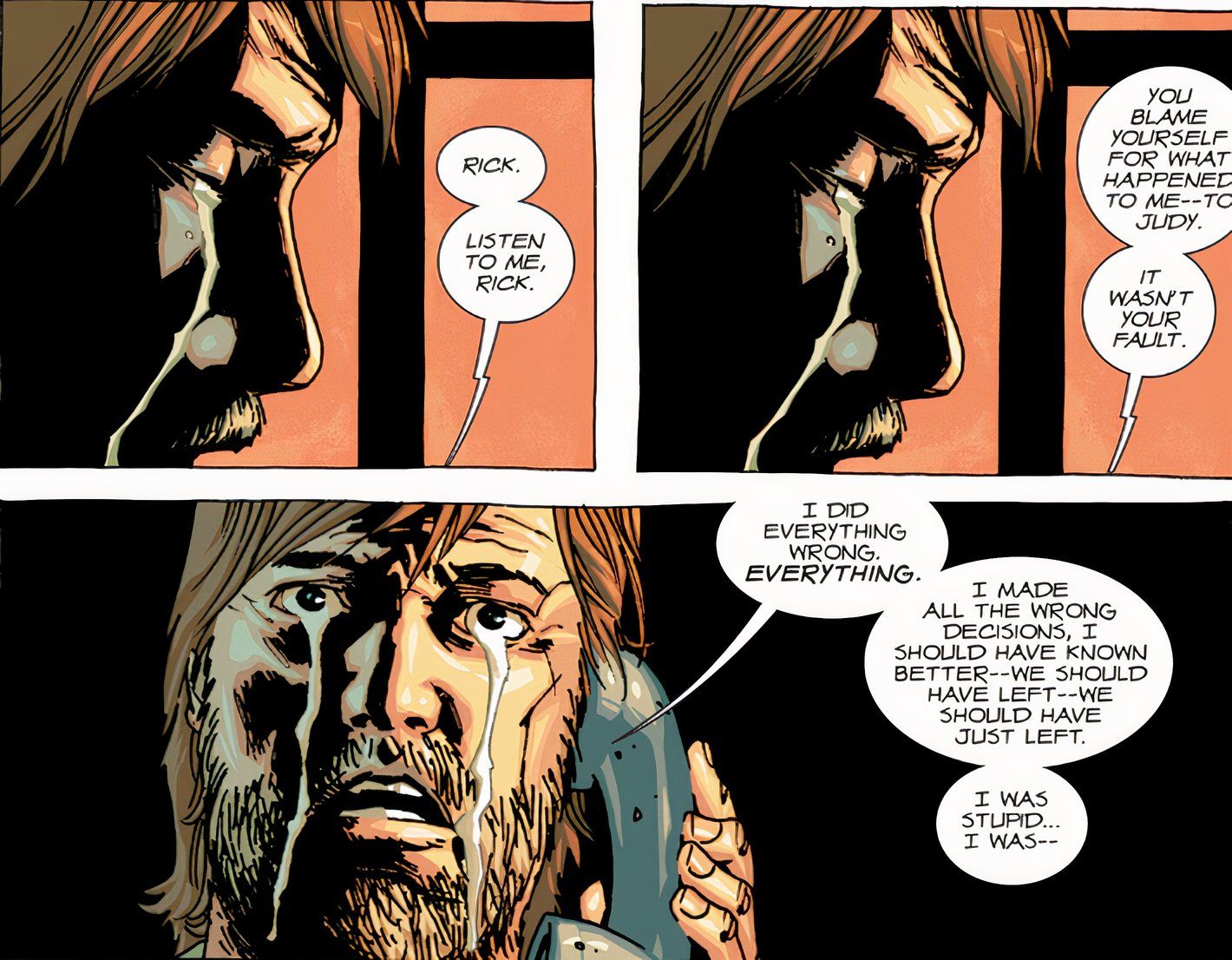

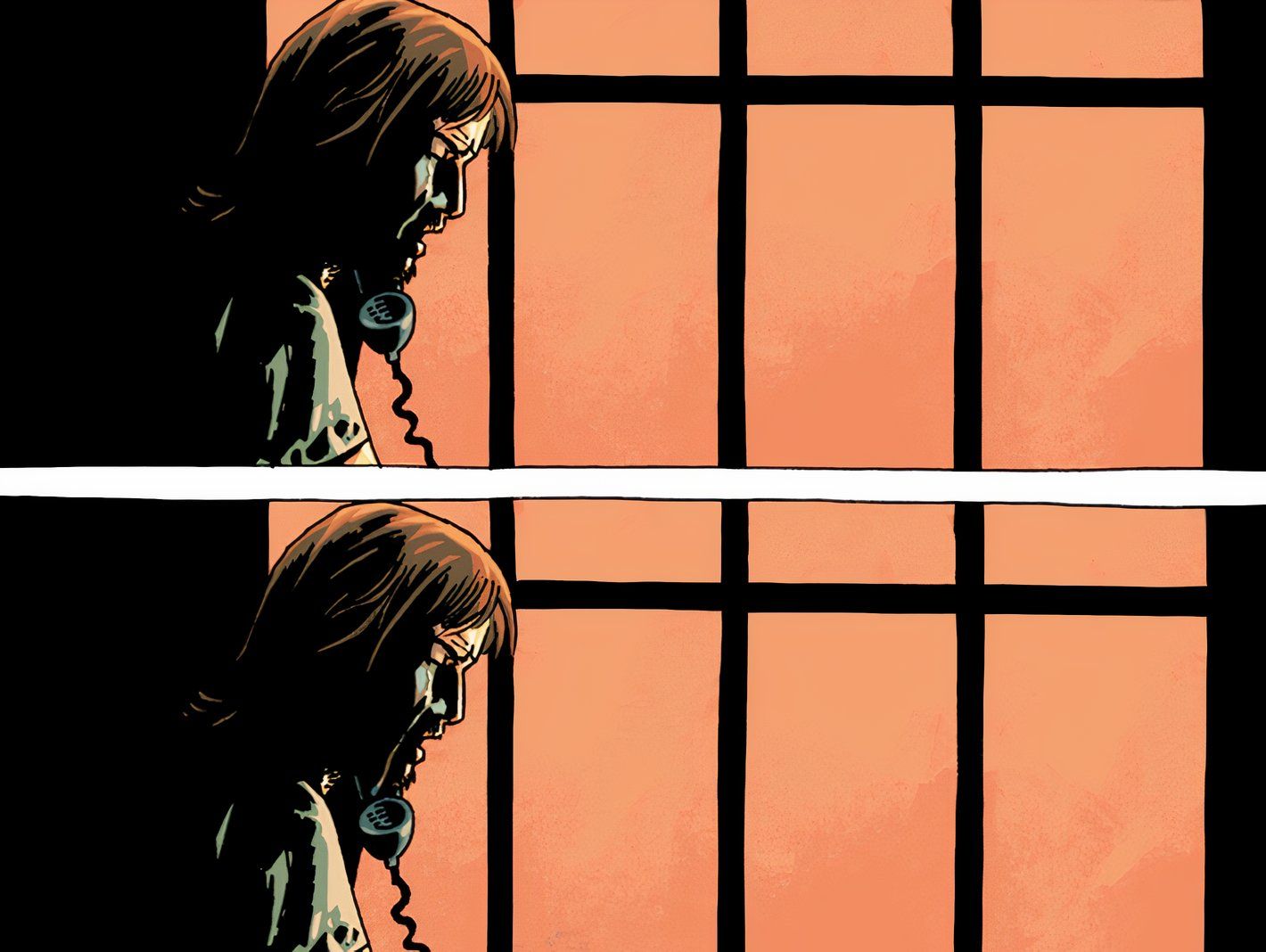

For instance, “Rick talking to a broken phone” was Robert Kirkman’s most evocative use of the device; arguably the protagonist of The Walking Dead, Rick Grimes’ one-sided conversation with his dead wife Lori laid bare the fragility of a man who was tirelessly trying not just to keep himself and his son alive, but to keep human society itself from definitively coming apart. Michonne speaking to her sword, meanwhile, was a key character-building detail, which played a role in cementing her as a fan-favorite.

With Andrea speaking to Dale’s hat, as Kirkman points out, even at the time of scripting The Walking Dead #91, the author seemed to have become self-aware of how he was using the trope, and at least subtly undermined it. While these examples might exhibit a degradation of narrative effectiveness, it is arguable whether the trope can truly be said to have been overused, to the point of truly being recognized as a cliché. In each cited case, there was a reason for the scene; more generally, there is a creative rationale behind Robert Kirkman’s employment of the device.

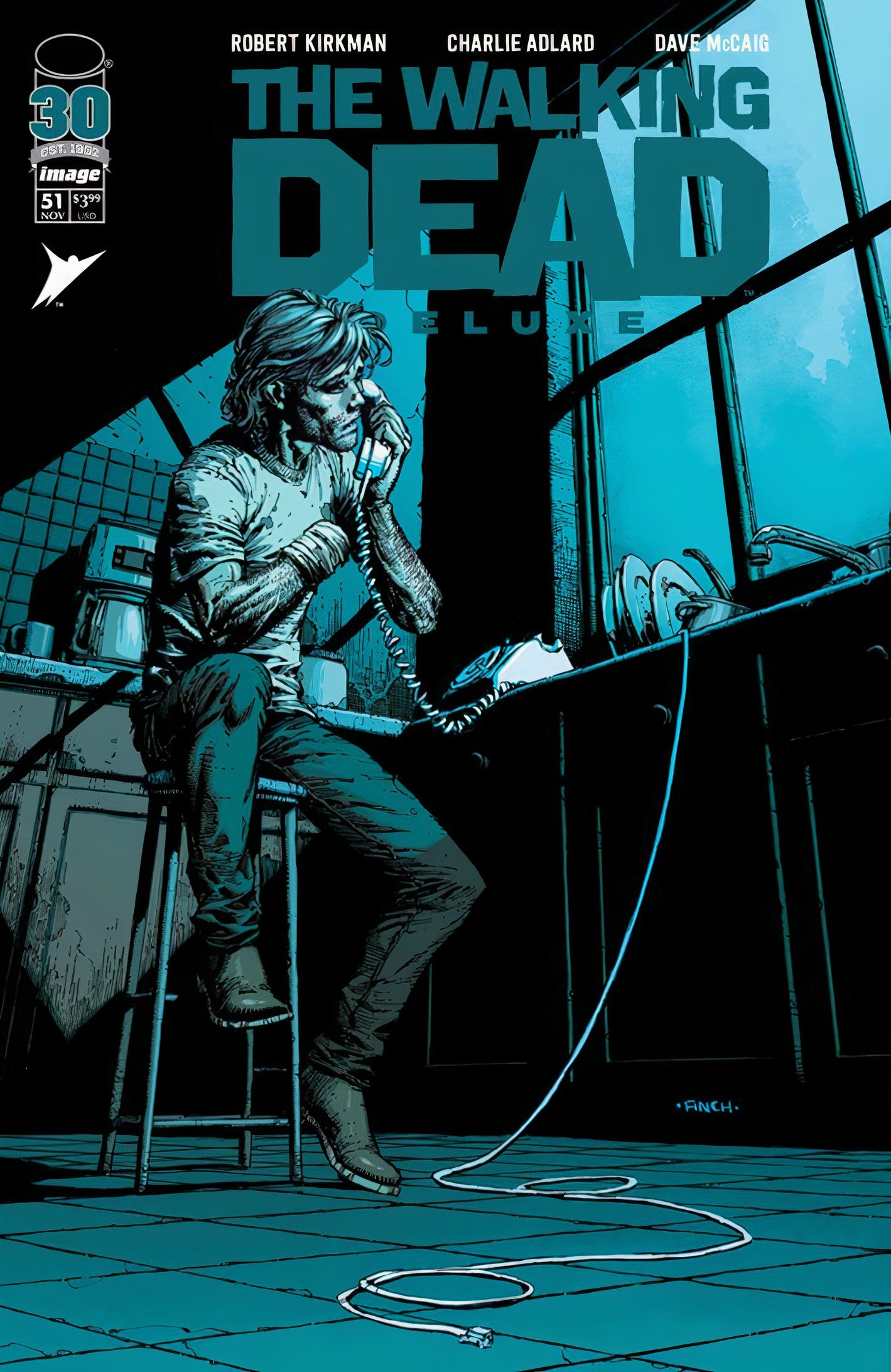

Rick Grimes’ telephone conversation with the disembodied voice of his dead wife Lori took place in The Walking Dead #51, a full forty issues before Andrea briefly talked to Dale’s hat in the wake of his death.

The Walking Dead’s Characters Needed A Way To Express Themselves

The Walking Dead Deluxe #51 – Written By Robert Kirkman; Art By Charlie Adlard; Color By Dave McCaig; Lettering By Rus Wooten

To whatever extent he used the device, and however effective each instance was, Robert Kirkman having his characters talk to inanimate objects was a way of having them actively express themselves, while engaging with the world around them.

It is worth taking a look at the franchise’s use of the “talking-to-an-object” trope in more detail, in the context of Kirkman’s comments. Though he describes the repeated occurrences of the technique “a bit much,” it is important to consider both the “why” and “how” of the trope’s appearance in The Walking Dead. In comics, dialogue is a primary, driving force – and because the comic series contained minimal narration, and almost no character interiority, at times, Robert Kirkman needed to find ways to have the characters express themselves, without having them talk to other characters.

In any piece of fiction –but especially one that is action-oriented, and drama-forward, like The Walking Dead – it is essential to have active, rather than passive characters. To whatever extent he used the device, and however effective each instance was, Robert Kirkman having his characters talk to inanimate objects was a way of having them actively express themselves, while engaging with the world around them. While in a novel, Rick or Michonne could simply break into a monologue, the comic book medium called for some kind of intermediary device, to facilitate their one-sided conversation.

Rick’s use of the broken phone stands out because it is a recognizable visual; further, it represents Rick’s yearning not just for his dead wife, but also for some measure of long-gone normalcy, such as a telephone call. If Michonne talking to her sword, or Andrea talking to Dale’s hat, are less effective, it is not because they are repetitions of this trope, but because they don’t offer the same layered visual and emotional meaning of Rick Grimes’ phantom telephone calls.

Kirkman also compared his use of this device to the TV adaptation’s use of graffiti to convey information, writing: “Like Scott Gimple’s ‘people write something on a wall somewhere’ crutch on the show. Love you, Scott!

Kirkman’s Insights Into The Walking Dead Add Depth To The “Deluxe” Reprint

Exciting New Context For The Classic Series

[Kirkman’s use of the trope] gave them space to forward their emotional arcs in particular ways, to process their traumas and develop as more complex figures, in ways that their dialogue with other characters might not.

The Walking Dead was saturated in death, and its characters were in constant mourning; in other words, it makes a certain degree of sense that similar coping mechanisms would be portrayed in parallel. This is one reason that Robert Kirkman’s repeated use of the narrative device can be defended. More than just offering a reason for a character to monologue, it gave them space to forward their emotional arcs in particular ways, to process their traumas and develop as more complex figures, in ways that their dialogue with other characters might not.

It is understandable that over a decade later, and with much more creative experience under his belt, Robert Kirkman has developed a more refined authorial sense. Applying this to his own work in The Walking Dead – the series that elevated him to one of the foremost comic book creators in contemporary pop culture – has been the most fascinating part of The Walking Dead Deluxe. However, readers should interpret his analysis of his own earlier creative decision in the same way they would the creative decisions on the page themselves.

Kirkman’s Take On Walking Dead Shouldn’t Color Readers’ Opinions Too Much

Putting The Author’s Intent In Perspective

Ultimately, it is up to readers to decide for themselves if the “character talks to inanimate object” trope was overused in The Walking Dead , or if each instance justified itself in its own way.

As grateful as fans should be for it, Kirkman’s reading of The Walking Dead should be looked at not as authoritative, but as the opinion of a highly-qualified expert. This distinction is critical; it is incredibly valuable to readers – and emerging creators who look up to Robert Kirkman – to have him offer such a high-level dissection of his own creative process, and its result. At the same time, just as with any author, his statements should not always override individual readers’ interpretations of his work.

Ultimately, it is up to readers to decide for themselves if the “character talks to inanimate object” trope was overused in The Walking Dead, or if each instance justified itself in its own way. Given the opportunity, Robert Kirkman might not have employed this narrative device as many times as he did. However, if he hadn’t at the time, he might not have arrived at a scene like the one in which Rick talks to Lori on the phone, which holds up as one of The Walking Dead’s most heartbreaking moments.