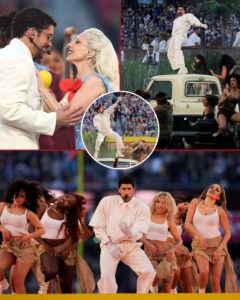

Just minutes before the kickoff of Super Bowl LX on February 9, 2026, the Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta was already electric. The crowd of 70,000+ had spent the pre-game buildup anticipating spectacle, guest stars, and the kind of larger-than-life production Apple Music’s halftime shows have become known for. What no one — not the fans in the stands, not the millions watching at home, not even the most plugged-in insiders — fully expected was that Bad Bunny would turn the halftime stage into something far more intimate and far more powerful: a full-throated, unapologetic love letter to Puerto Rico, delivered at the exact moment the entire planet was watching.

The performance began in near darkness. A single spotlight hit the center of the field. Bad Bunny — Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio — walked out alone, wearing a simple white guayabera embroidered with the Puerto Rican flag across the chest, black pants, and black boots. No dancers, no elaborate set pieces, no pyrotechnics. Just him, a microphone, and the opening chords of “Tití Me Preguntó.” The beat dropped — that unmistakable reggaeton pulse — and the stadium erupted.

From the very first line, it was clear this would not be a conventional halftime show. Bad Bunny didn’t open with a medley of his biggest global hits designed to maximize crossover appeal. He opened with songs that carried stories, culture, and pride — songs that meant something specific to Puerto Ricans and Latin Americans everywhere. “Tití Me Preguntó” rolled into “Yo Perreo Sola,” the anthem of female empowerment and queer liberation that had become a cultural touchstone years earlier. The crowd sang every word, phones up, lights waving like a sea of stars.

Then came the moment that shifted the entire night.

The stage lights dimmed again. A massive screen behind him lit up with archival footage: black-and-white images of Old San Juan, the beaches of Rincón, the mountains of El Yunque, families dancing bomba and plena, children playing in the streets of La Perla. Bad Bunny stood motionless as the music faded to a low, pulsing bassline. When he spoke, his voice was soft but carried through the stadium speakers like a whisper that everyone heard.

“This is for Puerto Rico,” he said, switching to Spanish for the first time. “For everyone who left, and everyone who stayed. For the ones who rebuilt after the storms, after the earthquakes, after everything. This is ours.”

The arena — already loud — became thunderous. The camera panned across the stands: Puerto Rican flags waving, tears on faces, arms raised. Bad Bunny then launched into “DtMF” (Diles Todo Mi Flow), the track that had become an unofficial anthem of resilience after Hurricane Maria. The stage transformed: projections of the Puerto Rican flag rippled across the field, palm trees swayed in virtual wind, and the silhouette of El Morro appeared behind him. The beat dropped harder, the horns kicked in, and Bad Bunny moved with the same restless energy that has defined his career — but this time it felt different. It wasn’t performance. It was testimony.

The set list unfolded like a love letter:

“Moscow Mule” and “Efecto” brought the party energy back, with dancers in traditional Puerto Rican bomba costumes joining him for a choreography that fused reggaeton with folkloric steps.

“Un Ratito” and “Neverita” turned the stadium into a giant dance floor — even the luxury boxes were swaying.

A surprise appearance by Residente for a fiery verse on “Bellacoso” reminded everyone that Bad Bunny has always used his platform to speak about Puerto Rican identity, colonialism, and resistance.

The emotional peak came with “Andrea,” performed solo with just an acoustic guitar. The song — about a woman trapped in a cycle of abuse and societal pressure — hit harder in the context of the night: a reminder that pride and pain often walk hand in hand.

The final sequence was pure catharsis. The stage filled with hundreds of Puerto Rican flags handed out to the audience earlier in the day. Bad Bunny stood center stage as the entire stadium waved them in unison. He closed with “Safaera,” the chaotic, genre-blending monster track that has become a live staple, turning the field into a celebration of Puerto Rican musical diversity — reggaeton, salsa, bomba, plena, trap, all colliding in one glorious, sweaty mess.

When the final note rang out, Bad Bunny dropped to one knee, head bowed, hand on his heart. The stadium lights came up slowly. The crowd stayed on their feet for more than three minutes — not cheering wildly, but singing the chorus of “Safaera” a cappella until the house lights rose completely.

Post-show reactions were overwhelming. The performance trended globally for 48 straight hours. Clips of the Puerto Rican flag wave, Bad Bunny kneeling, and the moment he switched to Spanish mid-set were shared millions of times. Puerto Rican flags sold out online within hours. The hashtag #PuertoRicoEnElSuperBowl trended worldwide, and Bad Bunny’s streaming numbers spiked across the board.

Critics and commentators called it one of the most culturally significant halftime shows in Super Bowl history — a rare instance when the platform was used not just for entertainment, but for unapologetic cultural affirmation. For many Puerto Ricans watching from the island and the diaspora, it was the first time they had seen their culture celebrated so fully on the biggest stage in American media.

Bad Bunny himself said little after the show. In a short Instagram post the next morning he wrote only:

“Gracias, Puerto Rico. Siempre contigo. 🇵🇷”

No explanation needed.

The performance didn’t just entertain — it reminded a massive audience that identity, pride, and resilience are not side notes in entertainment. They are the heartbeat.

And on that Sunday night in Atlanta, the heartbeat of Puerto Rico was loud, proud, and impossible to ignore.