Mike Tyson is running late for dinner. He opens the back door of his guesthouse, his broad frame filling the doorway. His wife, Kiki, looks up as he shuffles over to her in the small kitchen and gives her a kiss. “Am I eating tonight, or am I finished eating?” Tyson asks. She’s sitting on a stool in yoga pants, toweling off her hair. “I got you Nobu,” she says. “What’d you get me?” he asks. “I got you your fish,” she says. “The fish I like?” They’re in the guesthouse because their actual house, a sprawling mansion in Henderson, a residential suburb of Las Vegas, is under construction. Instead of flopping off to a hotel, where fans would flock, they’ve retreated here. Mars, their fluffy goldendoodle, makes his rounds of the room. From the speakers, a Balinese-style rhythm pulses, soft and hypnotic.

It’s almost surreal to imagine that this version of Tyson — comfortable, gray-stubbled, and 58 — will be fighting again soon. Officially, he retired from boxing nearly 20 years ago when he refused to come off his stool against the inferior Kevin McBride (“I don’t have the fighting guts anymore,” he said then). At that time, his upcoming opponent, Jake Paul, the internet celebrity turned boxer, was making his way through elementary school. Paul is now all grown up and preparing to take on Tyson November 15 under the lights of AT&T Stadium in Arlington, Texas. The fight, which will be streamed on Netflix, has special rules: eight rounds, two minutes per rounder, and slightly cushier 14-ounce gloves. The matchup could become one of the most watched sports events of the year and one of the most lucrative. There’s speculation that Netflix has paid $80 million in purses alone for the fight; if that’s even close to being true, it could rival the figures Tyson made in his pay-per-view prime.

The fight was originally scheduled for July 20. Training for it the first time nearly killed Tyson. He was on a flight to Los Angeles from Miami when he suddenly passed out. “When I came to,” he says, “I was in the bathroom throwing up blood.” After the plane landed at LAX, he was taken to the hospital. The doctors looked panicked, he says; Kiki was crying. “I asked the doctor, ‘Am I going to die?’” Tyson says, putting his head in his hands. “He said, ‘We have options.’ Options? I couldn’t believe it.” Tyson was treated for what turned out to be a bleeding ulcer. The recovery was brutal. “I lost 25 pounds in 11 days,” he says. “Couldn’t eat. Only liquids. Every time I went to the bathroom, it smelled like tar. Didn’t even smell like shit anymore. It was disgusting.” When he finally returned home, his body was wrecked, all his hard training gone. “It threw me off,” he says of the episode. “All my coordination, stamina, everything was hectic getting back. I was peaked already. I could have fought him that day. Now I got to start from scratch.” The full story never made the press. The promoters simply said he’d had an ulcer “flare-up” and postponed the bout to the fall. “I had, like, eight blood transfusions,” he says. “The doctor said I lost half my blood. I almost died.”

In the guesthouse, the microwave dings. Tyson makes his way to the breakfast bar and digs into his miso cod; the fork looks tiny in a set of massive hands that have, over the years, knocked out 44 opponents. Kiki pops her head out from behind the counter to offer tea. As the water boils, we talk about what makes this relationship — one that has helped rescue Tyson’s career — work for her. “I’m so attracted to him because he’s not afraid to self-reflect and be vulnerable,” she says. “Mike has so many layers.” She continues, a positivity machine: “I adore him, not just as my husband, but like he’s my baby, too.”

They’ve known each other for decades. She was only a teenager when they first met in the ’90s. Tyson, then the youngest heavyweight champion of the world, had recently embraced Islam in prison after his 1992 rape conviction; Kiki’s step-father, Shamsud-din Ali, was a powerful imam in Philadelphia.

In 1996, as Tyson prepared to fight Frank Bruno to defend his heavyweight title, Kiki and her parents briefly stayed with Tyson at his mansion in Ohio, according to his memoir. It was the ultimate bachelor pad with custom cages for Tyson’s Bengal tigers and a massive boxing-glove-shaped pool — and it was where the couple first became romantically involved. Soon after, Tyson gifted Kiki a Chopard diamond elephant pendant. “It wasn’t expensive, only $65,000 or so,” Tyson writes in Undisputed Truth, his 2013 memoir. “I would give shit like that to a homeless person.” He would go on to marry and have two children with Dr. Monica Turner and have relationships with several other women, but he and Kiki stayed in touch. When Tyson lost to heavyweight champ Lennox Lewis in 2002, Kiki was there to nurse his wounds. And when Tyson’s drug addiction got bad, she came back again. His downward spiral from drugs was so steep that one of his closest friends, Zip, began setting money aside to prepare for his funeral. “I’m going to get one of those carriages the horses pull around, and we’ll have your casket behind it,” Zip told him. “We’re going to flaunt your body through all the boroughs of the city, man. It’s going to be beautiful.” A self-described “relapse artist,” Tyson cycled through rehab programs and was banned from hotels on the Las Vegas Strip. His weight ballooned to almost 400 pounds. His closest friends credit Kiki with saving his life. “She knows who I am,” Tyson says. “She knows my flaws. And we know each other’s flaws.”

After a 2005 federal investigation into her stepfather’s business dealings in Philly, and while pregnant with their first daughter, Milan, Kiki wound up serving prison time for fraud and conspiracy. When she got out, Tyson was still struggling. She looked after their young child while he went through another bout in rehab. Then Tyson’s daughter from another relationship, Exodus, died in a tragic accident. The loss changed everything for him. He and Kiki got married; Tyson got closer to sobriety. Tyson’s addiction and recovery had been costly, so they lived in a cramped townhouse in Vegas with Kiki’s mother, where they binged episodes of Law & Order and played trivia games; Tyson, a sugar fiend, would also binge on cookies and Cap’n Crunch. Kiki says she was happy during this time, despite everything they’d been through. “I’ve been happiest at my brokest,” she says, sipping tea. “Mike used to get so annoyed, asking me, ‘What are you so happy about?’” “Yeah,” he says, “I didn’t get it. We got no food.” She turns to him, her eyes warm. “I was so happy just to have another day with you,” she says. “He’s on the happiness train now, though.”

Bit by bit, Kiki began to overhaul Tyson’s health. She studied the cocktail of meds he was on — Cymbalta for depression, Depakote for bipolar disorder, Neurontin for epilepsy — horrified at their adverse side effects. So she weaned him off them and put him on Chinese herbs instead. They experimented with veganism and went to yoga, and soon Tyson was losing weight. He began experimenting with psychedelics. “I’ve done the toad 16 times,” he said in 2020 on Logan Paul’s podcast. “You want to experience being God for a few minutes? That’s what it does: introduce you to God. You want to meet some of your ancestors? You want to meet people who died recently who you love? Hang with the toad.” Kiki took over his business affairs, too, helping develop a one-man show with Spike Lee based on Tyson’s memoir, then directing him onstage through an earpiece when it premiered.

Together, Kiki and Tyson created a growing portfolio of businesses: an apparel brand, a boxing-glove brand, a cannabis company called Tyson 2.0. They founded a charity to help children in need and invested in a vegan fast-food chain. “She’s one of the most impressive and toughest women I’ve ever met in business,” says Adam Wilks, Tyson 2.0’s CEO. The company is now growing so quickly — with cannabis products in more than 20 states and 19 countries — that Wilks moved part time to Nevada to be closer to the family. The tenderness between Tyson and Kiki still surprises him. “We’ve been at dinner where Mike just laid his head in her lap,” Wilks says. “It’s amazing how the toughest man on the planet can drop the badass.”

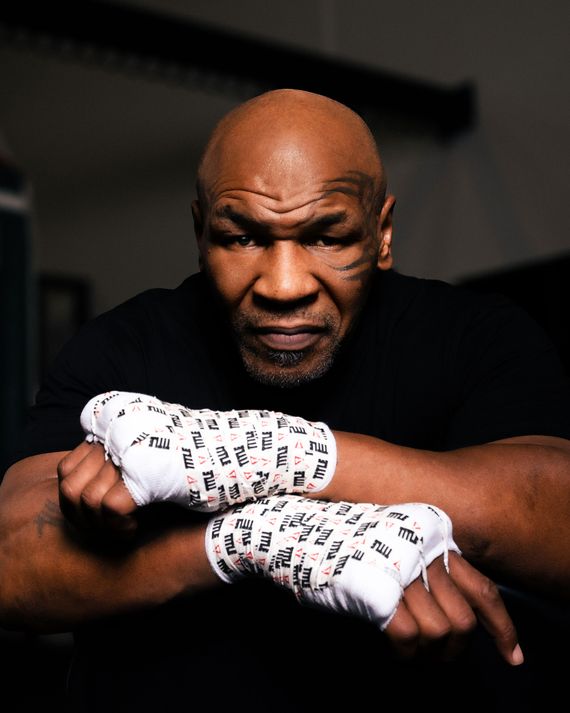

Once his doctors cleared him to train in late July, Tyson retreated once again to his cavernous gym in the back of the Las Vegas Raiders’ facility. There are no steady working hours here. On days off and in the middle of the night, Tyson is known to call his trainers, wanting to hit the pads and work out. The space, gifted to him by Mark Davis, the majority owner of the Raiders and a longtime friend of Tyson’s, feels part theater, part temple. Black curtains hang from the ceiling around rows of gleaming workout equipment. Full-length mirrors line the walls. At the center of it all, a boxing ring rises like a stage, surrounded by soft leather chairs for the few allowed in. Just behind sits a boom box, ready to blast the oldies, such as Sam Cooke and Barry White, that Tyson likes. Nearby is a smoothie bar and a space for watching movies or playing video games. It’s a five-star man cave designed to keep Tyson in his zone. Amid it all hangs the Willie, a heavy bag that his first pro trainer, Cus D’Amato, invented. It has its own numerical system for punches — odd numbers for left-hand punches, even numbers for right. In the distance is a poster with a quote Tyson borrowed from D’Amato: “Discipline is doing what you hate to do, but doing it like you love it.”

The gym doubles as a content studio. While he trains, his creative-content producer, Mike Angel, floats around, capturing moments of Tyson’s sessions to upload. He is training harder than in his prime, his team says, with a daily regimen that includes running four miles on the treadmill, 7,000 pulls on the rowing machine, and sparring. Training this Mike Tyson — given the freshly healed ulcer that nearly killed him — is like restoring an ancient sculpture, carefully brushing away the dust of time, hoping nothing breaks. “Mike is a masterpiece,” Rafael Cordeiro, one of his trainers, tells me. “Nobody can teach him to box. We just maintain the rhythm of what he does best.” Jake Paul has not been a pro boxer for long, but the advantages of youth cannot be overlooked. His best punches — an overhand right and right uppercut — are dangerous. He has ten wins and one loss, many of them against UFC stars. Any slight misstep, for both, could be costly.

The physical risks are obvious, but there is also a threat to the Tyson legacy. For all his toughness and talent, Tyson’s greatest vulnerability has always been his self-esteem, a glitchy operating system shadowed by doubt. Getting knocked out by an internet celebrity could crash the mainframe. “You can’t come from where I come from and not have low self-esteem,” Tyson tells me in the gym. “I don’t care if you have trillions of dollars. It doesn’t matter. It haunts you. Your low self-esteem haunts you.” His voice trembles while he thinks about the past. “I think about it even to this day,” he says. “Why me? What the fuck is so special about me?” This feeling, he believes, is an unlikely source of inspiration. “Like me getting this fight,” he says of the Paul bout. “Sometimes I might feel like I’m nothing. So let me do this.”

The training has been fairly all-consuming, Kiki admits back at the guesthouse. She’s looking forward to its being over: “After that, we can be more of a unit.” Their daughter Milan is now 15 and off training with the elite tennis coach Patrick Mouratoglou in France. “She’s going to be No. 1,” Kiki says, her voice confident. Tyson, proud, adds, “Our daughter’s a novelist, too.” Their son, Morocco, is away, running track and playing golf in Florida, where they also have a home and he goes to school. In the meantime, Kiki has been picking out new tiles for the renovation. “I’ve ordered crystals for every room,” she says. “Rose quartz for love, jade for luck, and clear quartz for cleansing.” Tyson raises an eyebrow at the crystal tower on the coffee table. “What’s that big block for?” She smiles playfully. “That’s going in our bedroom.” I ask Tyson about his secret — to resilience or survival. “I just don’t give up,” he says. “I’m an asshole sometimes. I’m a dick. If I haven’t outlived my enemies, I’ve turned them into my friends.”